Editors Note

This is Book II – Part II of the thirty seven books in Plinys’ Natural History. In order to make the collection more accessible and easier to navigate, most of the books have been divided into several parts. This book has been divided into six parts:

Part I – On God, the World, the Planets, the Sun and the Moon

Part II – On Stars and their characteristics, Meteors, Comets and Solar or Lunar Eclipses

Part III – On Seasons, Weather, Winds, Thunder and Lightning

Part IV – On Weather, the Earth, Climate and Daylight

Part V – On Earthquakes, Islands evolution, and Effects of the Sea on Land

Part VI – On the Sea, Fire, Dimensions of the Earth and the Universe

Translated by John Bostock MD, F.R.S (1773-1846) and Henry T. Riley Esq., B.A. (1816-1878), first published 1855. No changes have been made to the text, however all footnotes have been removed.

CHAP. 13.—WHY THE SAME STARS APPEAR AT SOME TIMES MORE LOFTY AND AT OTHER TIMES MORE NEAR.

The above is an account of the aspects and the occultations of the planets, a subject which is rendered very complicated by their motions, and is involved in much that is wonderful; especially, when we observe that they change their size and colour, and that the same stars at one time approach the north, and then go to the south, and are now seen near the earth, and then suddenly approach the heavens. If on this subject I deliver opinions different from my predecessors, I acknowledge that I am indebted for them to those individuals who first pointed out to us the proper mode of inquiry; let no one then ever despair of benefiting future ages.

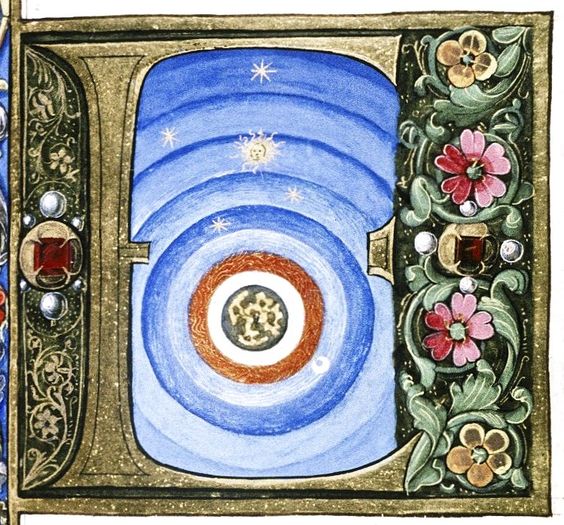

But these things depend upon many different causes. The first cause is the nature of the circles described by the stars, which the Greeks term apsides, for we are obliged to use Greek terms. Now each of the planets has its own circle, and this a different one from that of the world; because the earth is placed in the centre of the heavens, with respect to the two extremities, which are called the poles, and also in that of the zodiac, which is situated obliquely between them. And all these things are made evident by the infallible results which we obtain by the use of the compasses. Hence the apsides of the planets have each of them different centres, and consequently they have different orbits and motions, since it necessarily follows, that the interior apsides are the shortest.

The apsides which are the highest from the centre of the earth are, for Saturn, when he is in Scorpio, for Jupiter in Virgo, for Mars in Leo, for the Sun in Gemini, for Venus in Sagittarius, and for Mercury in Capricorn, each of them in the middle of these signs; while in the opposite signs, they are the lowest and nearest to the centre of the earth. Hence it is that they appear to move more slowly when they are carried along the highest circuit; not that their actual motions are accelerated or retarded, these being fixed and determinate for each of them; but because it necessarily follows, that lines drawn from the highest apsis must approach nearer to each other at the centre, like the spokes of a wheel; and that the same motion seems to be at one time greater, and at another time less, according to the distance from the centre.

Another cause of the altitudes of the planets is, that their highest apsides, with relation to their own centres, are in different signs from those mentioned above. Saturn is in the 20th degree of Libra, Jupiter in the 15th of Cancer, Mars in the 28th of Capricorn, the Sun in the 19th of Aries, Venus in the 27th of Pisces, Mercury in the 15th of Virgo, and the Moon in the 3rd of Taurus.

The third cause of the altitude depends on the form of the heavens, not on that of the orbits; the stars appearing to the eye to mount up and to descend through the depth of the air. With this cause is connected that which depends on the latitude of the planets and the obliquity of the zodiac. It is through this belt that the stars which I have spoken of are carried, nor is there any part of the world habitable, except what lies under it; the remainder, which is at the poles, being in a wild desert state. The planet Venus alone exceeds it by 2 degrees, which we may suppose to be the cause why some animals are produced even in these desert regions of the earth. The moon also wanders the whole breadth of the zodiac, but never exceeds it. Next to these the planet Mercury moves through the greatest space; yet out of the 12 degrees (for there are so many degrees of latitude in the zodiac), it does not pass through more than 8, nor does it go equally through these, 2 of them being in the middle of the zodiac, 4 in the upper part, and 2 in the lower part. Next to these the Sun is carried through the middle of the zodiac, winding unequally through the two parts of his tortuous circuit. The star Mars occupies the four middle degrees; Jupiter the middle degree and the two above it; Saturn, like the sun, occupies two. The above is an account of the latitudes as they descend to the south or ascend to the north. Hence it is plain that the generality of persons are mistaken in supposing the third cause of the apparent altitude to depend on the stars rising from the earth and climbing up the heavens. But to refute this opinion it is necessary to consider the subject with very great minuteness, and to embrace all the causes.

It is generally admitted, that the stars, at the time of their evening setting, are nearest to the earth, both with respect to latitude and altitude, that they are at the commencement of both at their morning risings, and that they become stationary at the middle points of their latitudes, what are called the ecliptics. It is, moreover, acknowledged, that their motion is increased when they are in the vicinity of the earth, and diminished when they are removed to a greater altitude; a point which is most clearly proved by the different altitudes of the moon. There is no doubt that it is also increased at the morning risings, and that the three superior planets are retarded, as they advance from the first station to the second. And since this is the case, it is evident, that the latitudes are increased from the time of their morning risings, since the motions afterwards appear to receive less addition; but they gain their altitude in the first station, since the rate of their motion then begins to diminish, and the stars to recede.

And the reason of this must be particularly set forth. When the planets are struck by the rays of the sun, in the situation which I have described, i. e. in their quadrature, they are prevented from holding on their straight forward course, and are raised on high by the force of the fire. This cannot be immediately perceived by the eye, and therefore they seem to be stationary, and hence the term station is derived. Afterwards the violence of the rays increases, and the vapour being beaten back forces them to recede.

This exists in a greater degree in their evening risings, the sun being then turned entirely from them, when they are drawn into the highest apsides; and they are then the least visible, since they are at their greatest altitude and are carried along with the least motion, as much less indeed as this takes place in the highest signs of the apsides. At the time of the evening rising the latitude decreases and becomes less as the motion is diminished, and it does not increase again until they arrive at the second station, when the altitude is also diminished; the sun’s rays then coming from the other side, the same force now therefore propels them towards the earth which before raised them into the heavens, from their former triangular aspect. So different is the effect whether the rays strike the planets from below or come to them from above. And all these circumstances produce much more effect when they occur in the evening setting. This is the doctrine of the superior planets; that of the others is more difficult, and has never been laid down by any one before me.

CHAP. 14.—WHY THE SAME STARS HAVE DIFFERENT MOTIONS.

I must first state the cause, why the star Venus never recedes from the sun more than 46 degrees, nor Mercury more than 23, while they frequently return to the sun within this distance. As they are situated below the sun, they have both of them their apsides turned in the contrary direction; their orbits are as much below the earth as those of the stars above mentioned are above it, and therefore they cannot recede any farther, since the curve of their apsides has no greater longitude. The extreme parts of their apsides therefore assign the limits to each of them in the same manner, and compensate, as it were, for the small extent of their longitudes, by the great divergence of their latitudes. It may be asked, why do they not always proceed as far as the 46th and the 23rd degrees respectively? They in reality do so, but the theory fails us here. For it would appear that the apsides are themselves moved, as they never pass over the sun. When therefore they have arrived at the extremities of their orbits on either side, the stars are then supposed to have proceeded to their greatest distance; when they have been a certain number of degrees within their orbits, they are then supposed to return more rapidly, since the extreme point in each is the same. And on this account it is that the direction of their motion appears to be changed. For the superior planets are carried along the most quickly in their evening setting, while these move the most slowly; the former are at their greatest distance from the earth when they move the most slowly, the latter when they move the most quickly. The former are accelerated when nearest to the earth, the latter when at the extremity of the circle; in the former the rapidity of the motion begins to diminish at their morning risings, in the latter it begins to increase; the former are retrograde from their morning to their evening station, while Venus is retrograde from the evening to the morning station. She begins to increase her latitude from her morning rising, her altitude follows the sun from her morning station, her motion being the quickest and her altitude the greatest in her morning setting. Her latitude decreases and her altitude diminishes from her evening rising, she becomes retrograde, and at the same time decreases in her altitude from her evening station.

Again, the star Mercury, in the same way, mounts up in both directions from his morning rising, and having followed the sun through a space of 15 degrees, he becomes almost stationary for four days. Presently he diminishes his altitude, and recedes from his evening setting to his morning rising. Mercury and the Moon are the only planets which descend for the same number of days that they ascend. Venus ascends for fifteen days and somewhat more; Saturn and Jupiter descend in twice that number of days, and Mars in four times. So great is the variety of nature! The reason of it is, however, evident; for those planets which are forced up by the vapour of the sun likewise descend with difficulty.

CHAP. 15.—GENERAL LAWS OF THE PLANETS.

There are many other secrets of nature in these points, as well as the laws to which they are subject, which might be mentioned. For example, the planet Mars, whose course is the most difficult to observe, never becomes stationary when Jupiter is in the trine aspect, very rarely when he is 60 degrees from the sun, which number is one-sixth of the circuit of the heavens; nor does he ever rise in the same sign with Jupiter, except in Cancer and Leo. The star Mercury seldom has his evening risings in Pisces, but very frequently in Virgo, and his morning risings in Libra; he has also his morning rising in Aquarius, very rarely in Leo. He never becomes retrograde either in Taurus or in Gemini, nor until the 25th degree of Cancer. The Moon makes her double conjunction with the sun in no other sign except Gemini, while Sagittarius is the only sign in which she has sometimes no conjunction at all. The old and the new moon are visible on the same day or night in no other sign except Aries, and indeed it has happened very seldom to any one to have witnessed it. Prom this circumstance it was that the tale of Lynceus’s quick-sightedness originated. Saturn and Mars are invisible at most for 170 days; Jupiter for 36, or, at the least, for 10 days less than this; Venus for 69, or, at the least, for 52; Mercury for 13, or, at the most, for 18.

CHAP. 16. —THE REASON WHY THE STARS ARE OF DIFFERENT COLOURS.

The difference of their colour depends on the difference in their altitudes; for they acquire a resemblance to those planets into the vapour of which they are carried, the orbit of each tinging those that approach it in each direction. A colder planet renders one that approaches it paler, one more hot renders it redder, a windy planet gives it a lowering aspect, while the sun, at the union of their apsides, or the extremity of their orbits, completely obscures them. Each of the planets has its peculiar colour; Saturn is white, Jupiter brilliant, Mars fiery, Lucifer is glowing, Vesper refulgent, Mercury sparkling, the Moon mild; the Sun, when he rises, is blazing, afterwards he becomes radiating. The appearance of the stars, which are fixed in the firmament, is also affected by these causes. At one time we see a dense cluster of stars around the moon, when she is only half-enlightened, and when they are viewed in a serene evening; while, at another time, when the moon is full, there are so few to be seen, that we wonder whither they are fled; and this is also the case when the rays of the sun, or of any of the above-mentioned bodies, have dazzled our sight. And, indeed, the moon herself is, without doubt, differently affected at different times by the rays of the sun; when she is entering them, the convexity of the heavens rendering them more feeble than when they fall upon her more directly. Hence, when she is at a right angle to the sun, she is half-enlightened; when in the trine aspect, she presents an imperfect orb, while, in opposition, she is full. Again, when she is waning, she goes through the same gradations, and in the same order, as the three stars that are superior to the sun.

CHAP. 17. —OF THE MOTION OF THE SUN AND THE CAUSE OF THE IRREGULARITY OF THE DAYS.

The Sun himself is in four different states; twice the night is equal to the day, in the Spring and in the Autumn, when he is opposed to the centre of the earth, in the 8th degree of Aries and Libra. The length of the day and the night is then twice changed, when the day increases in length, from the winter solstice in the 8th degree of Capricorn, and afterwards, when the night increases in length from the summer solstice in the 8th degree of Cancer. The cause of this inequality is the obliquity of the zodiac, since there is, at every moment of time, an equal portion of the firmament above and below the horizon. But the signs which mount directly upwards, when they rise, retain the light for a longer space, while those that are more oblique pass along more quickly.

CHAP. 18. —WHY THUNDER IS ASCRIBED TO JUPITER.

It is not generally known, what has been discovered by men who are the most eminent for their learning, in consequence of their assiduous observations of the heavens, that the fires which fall upon the earth, and receive the name of thunder-bolts, proceed from the three superior stars, but principally from the one which is situated in the middle. It may perhaps depend on the superabundance of moisture from the superior orbit communicating with the heat from the inferior, which are expelled in this manner; and hence it is commonly said, the thunder-bolts are darted by Jupiter. And as, in burning wood, the burnt part is cast off with a crackling noise, so does the star throw off this celestial fire, bearing the omens of future events, even the part which is thrown off not losing its divine operation. And this takes place more particularly when the air is in an unsettled state, either because the moisture which is then collected excites the greatest quantity of fire, or because the air is disturbed, as if by the parturition of the pregnant star.

CHAP. 19. —OF THE DISTANCES OF THE STARS.

Many persons have attempted to discover the distance of the stars from the earth, and they have published as the result, that the sun is nineteen times as far from the moon, as the moon herself is from the earth. Pythagoras, who was a man of a very sagacious mind, computed the distance from the earth to the moon to be 126,000 furlongs, that from her to the sun is double this distance, and that it is three times this distance to the twelve signs; and this was also the opinion of our countryman, Gallus Sulpicius.

CHAP. 20. —OF THE HARMONY OF THE STARS.

Pythagoras, employing the terms that are used in music, sometimes names the distance between the Earth and the Moon a tone; from her to Mercury he supposes to be half this space, and about the same from him to Venus. From her to the Sun is a tone and a half; from the Sun to Mars is a tone, the same as from the Earth to the Moon; from him there is half a tone to Jupiter, from Jupiter to Saturn also half a tone, and thence a tone and a half to the zodiac. Hence there are seven tones, which he terms the diapason harmony, meaning the whole compass of the notes. In this, Saturn is said to move in the Doric time, Jupiter in the Phrygian, and so forth of the rest; but this is a refinement rather amusing than useful.

CHAP. 21. —OF THE DIMENSIONS OF THE WORLD.

The stadium is equal to 125 of our Roman paces, or 625 feet. Posidonius supposes that there is a space of not less than 40 stadia around the earth, whence mists, winds and clouds proceed; beyond this he supposes that the air is pure and liquid, consisting of uninterrupted light; from the clouded region to the moon there is a space of 2,000,000 of stadia, and thence to the sun of 500,000,000. It is in consequence of this space that the sun, notwithstanding his immense magnitude, does not burn the earth. Many persons have imagined that the clouds rise to the height of 900 stadia. These points are not completely made out, and are difficult to explain; but we have given the best account of them that has been published, and if we may be allowed, in any degree, to pursue these investigations, there is one infallible geometrical principle, which we cannot reject. Not that we can ascertain the exact dimensions (for to profess to do this would be almost the act of a madman), but that the mind may have some estimate to direct its conjectures. Now it is evident that the orbit through which the sun passes consists of nearly 366 degrees, and that the diameter is always the third part and a little less than the seventh of the circumference. Then taking the half of this (for the earth is placed in the centre) it will follow, that nearly one-sixth part of the immense space, which the mind conceives as constituting the orbit of the sun round the earth, will compose his altitude. That of the moon will be one-twelfth part, since her course is so much shorter than that of the sun; she is therefore carried along midway between the sun and the earth. It is astonishing to what an extent the weakness of the mind will proceed, urged on by a little success, as in the above-mentioned instance, to give full scope to its impudence! Thus, having ventured to guess at the space between the sun and the earth, we do the same with respect to the heavens, because he is situated midway between them; so that we may come to know the measure of the whole world in inches. For if the diameter consist of seven parts, there will be twenty-two of the same parts in the circumference; as if we could measure the heavens by a plumb-line!

The Egyptian calculation, which was made out by Petosiris and Necepsos, supposes that each degree of the lunar orbit (which, as I have said, is the least) consists of little more than 33 stadia; in the very large orbit of Saturn the number is double; in that of the sun, which, as we have said, is in the middle, we have the half of the sum of these numbers. And this is indeed a very modest calculation, since if we add to the orbit of Saturn the distance from him to the zodiac, we shall have an infinite number of degrees.

CHAP. 22. —OF THE STARS WHICH APPEAR SUDDENLY, OR OF COMETS.

A few things still remain to be said concerning the world; for stars are suddenly formed in the heavens themselves; of these there are various kinds.

The Greeks name these stars comets; we name them Crinitæ, as if shaggy with bloody locks, and surrounded with bristles like hair. Those stars, which have a mane hanging down from their lower part, like a long beard, are named Pogoniæ. Those that are named Acontiæ vibrate like a dart with a very quick motion. It was one of this kind which the Emperor Titus described in his very excellent poem, as having been seen in his fifth consulship; and this was the last of these bodies which has been observed. When they are short and pointed they are named Xiphiæ; these are the pale kind; they shine like a sword and are without any rays; while we name those Discei, which, being of an amber colour, in conformity with their name, emit a few rays from their margin only. A kind named Pitheus exhibits the figure of a cask, appearing convex and emitting a smoky light. The kind named Cerastias has the appearance of a horn; it is like the one which was visible when the Greeks fought at Salamis. Lampadias is like a burning torch; Hippias is like a horse’s mane; it has a very rapid motion, like a circle revolving on itself. There is also a white comet, with silver hair, so brilliant that it can scarcely be looked at, exhibiting, as it were, the aspect of the Deity in a human form. There are some also that are shaggy, having the appearance of a fleece, surrounded by a kind of crown. There was one, where the appearance of a mane was changed into that of a spear; it happened in the 109th olympiad, in the 398th year of the City. The shortest time during which any one of them has been observed to be visible is 7 days, the longest 180 days.

CHAP. 23.—THEIR NATURE, SITUATION, AND SPECIES.

Some of them move about in the manner of planets, others remain stationary. They are almost all of them seen towards the north, not indeed in any particular portion of it, but generally in that white part of it which has obtained the name of the Milky Way. Aristotle informs us that several of them are to be seen at the same time, but this, as far as I know, has not been observed by any one else; also that they prognosticate high winds and great heat. They are also visible in the winter months, and about the south pole, but they have no rays proceeding from them. There was a dreadful one observed by the Æthiopians and the Egyptians, to which Typhon, a king of that period, gave his own name; it had a fiery appearance, and was twisted like a spiral; its aspect was hideous, nor was it like a star, but rather like a knot of fire. Sometimes there are hairs attached to the planets and the other stars. Comets are never seen in the western part of the heavens. It is generally regarded as a terrific star, and one not easily expiated; as was the case with the civil commotions in the consulship of Octavius, and also in the war of Pompey and Cæsar. And in our own age, about the time when Claudius Cæsar was poisoned and left the Empire to Domitius Nero, and afterwards, while the latter was Emperor, there was one which was almost constantly seen and was very frightful. It is thought important to notice towards what part it darts its beams, or from what star it receives its influence, what it resembles, and in what places it shines. If it resembles a flute, it portends something unfavourable respecting music; if it appears in the parts of the signs referred to the secret members, something respecting lewdness of manners; something respecting wit and learning, if they form a triangular or quadrangular figure with the position of some of the fixed stars; and that someone will be poisoned, if they appear in the head of either the northern or the southern serpent.

Rome is the only place in the whole world where there is a temple dedicated to a comet; it was thought by the late Emperor Augustus to be auspicious to him, from its appearing during the games which he was celebrating in honour of Venus Genetrix, not long after the death of his father Cæsar, in the College which was founded by him. He expressed his joy in these terms: “During the very time of these games of mine, a hairy star was seen during seven days, in the part of the heavens which is under the Great Bear. It rose about the eleventh hour of the day, was very bright, and was conspicuous in all parts of the earth. The common people supposed the star to indicate, that the soul of Cæsar was admitted among the immortal Gods; under which designation it was that the star was placed on the bust which was lately consecrated in the forum.” This is what he proclaimed in public, but, in secret, he rejoiced at this auspicious omen, interpreting it as produced for himself; and, to confess the truth, it really proved a salutary omen for the world at large.

Some persons suppose that these stars are permanent, and that they move through their proper orbits, but that they are only visible when they recede from the sun. Others suppose that they are produced by an accidental vapour together with the force of fire, and that, from this circumstance, they are liable to be dissipated.

CHAP. 24. —THE DOCTRINE OF HIPPARCHUS ABOUT THE STARS.

This same Hipparchus, who can never be sufficiently commended, as one who more especially proved the relation of the stars to man, and that our souls are a portion of heaven, discovered a new star that was produced in his own age, and, by observing its motions on the day in which it shone, he was led to doubt whether it does not often happen, that those stars have motion which we suppose to be fixed. And the same individual attempted, what might seem presumptuous even in a deity, viz. to number the stars for posterity and to express their relations by appropriate names; having previously devised instruments, by which he might mark the places and the magnitudes of each individual star. In this way it might be easily discovered, not only whether they were destroyed or produced, but whether they changed their relative positions, and likewise, whether they were increased or diminished; the heavens being thus left as an inheritance to one, who might be found competent to complete his plan.

CHAP. 25.—EXAMPLES FROM HISTORY OF CELESTIAL PRODIGIES; FACES, LAMPADES, AND BOLIDES.

The faces shine brilliantly, but they are never seen excepting when they are falling; one of these darted across the heavens, in the sight of all the people, at noon-day, when Germanicus Cæsar was exhibiting a show of gladiators. There are two kinds of them; those which are called lampades and those which are called bolides, one of which latter was seen during the troubles at Mutina. They differ from each other in this respect, that the faces produce a long train of light, the fore-part only being on fire; while the bolides, being entirely in a state of combustion, leave a still longer track behind them.

CHAP. 26.—TRABES CELESTES; CHASMA CŒLI.

The trabes also, which are named δοκοὶ, shine in the same manner; one of these was seen at the time when the Lacedæmonians, by being conquered at sea, lost their influence in Greece. An opening sometimes takes place in the firmament, which is named chasma.

CHAP. 27. —OF THE COLOURS OF THE SKY AND OF CELESTIAL FLAME.

There is a flame of a bloody appearance (and nothing is more dreaded by mortals) which falls down upon the earth, such as was seen in the third year of the 103rd olympiad, when King Philip was disturbing Greece. But my opinion is, that these, like everything else, occur at stated, natural periods, and are not produced, as some persons imagine, from a variety of causes, such as their fine genius may suggest. They have indeed been the precursors of great evils, but I conceive that the evils occurred, not because the prodigies took place, but that these took place because the evils were appointed to occur at that period. Their cause is obscure in consequence of their rarity, and therefore we are not as well acquainted with them as we are with the rising of the stars, which I have mentioned, and with eclipses and many other things.

CHAP. 28. —OF CELESTIAL CORONÆ.

Stars are occasionally seen along with the sun, for whole days together, and generally round its orb, like wreaths made of the ears of corn, or circles of various colours; such as occurred when Augustus, while a very young man, was entering the city, after the death of his father, in order to take upon himself the great name which he assumed. (29.) The same coronæ occur about the moon and also about the principal stars, which are stationary in the heavens.

CHAP. 29.—OF SUDDEN CIRCLES.

A bow appeared round the sun in the consulship of L. Opimius and L. Fabius, and a circle in that of C. Porcius and M. Acilius. (30.) There was a little circle of a red colour in the consulship of L. Julius and P. Rutilius.

CHAP. 30.—OF UNUSUALLY LONG ECLIPSES OF THE SUN.

Eclipses of the sun also take place which are portentous and unusually long, such as occurred when Cæsar the Dictator was slain, and in the war against Antony, the sun remained dim for almost a whole year.

CHAP. 31. —MANY SUNS.

And again, many suns have been seen at the same time; not above or below the real sun, but in an oblique direction, never near nor opposite to the earth, nor in the night, but either in the east or in the west. They are said to have been seen once at noon in the Bosphorus, and to have continued from morning until sunset. Our ancestors have frequently seen three suns at the same time, as was the case in the consulship of Sp. Postumius and L. Mucius, of L. Marcius and M. Portius, that of M. Antony and Dolabella, and that of M. Lepidus and L. Plancus. And we have ourselves seen one during the reign of the late Emperor Claudius, when he was consul along with Corn. Orfitus. We have no account transmitted to us of more than three having been seen at the same time.

CHAP. 32. —MANY MOONS.

Three moons have also been seen, as was the case in the consulship of Cn. Domitius and C. Fannius; they have generally been named nocturnal suns.

CHAP. 33. —DAYLIGHT IN THE NIGHT.

A bright light has been seen proceeding from the heavens in the night time, as was the case in the consulship of C. Cæcilius and Cn. Papirius, and at many other times, so that there has been a kind of daylight in the night.

CHAP. 34. —BURNING SHIELDS.

A burning shield darted across at sunset, from west to east, throwing out sparks, in the consulship of L. Valerius and C. Marius.

CHAP. 35. —AN OMINOUS APPEARANCE IN THE HEAVENS, THAT WAS SEEN ONCE ONLY.

We have an account of a spark falling from a star, and increasing as it approached the earth, until it became of the size of the moon, shining as through a cloud; it afterwards returned into the heavens and was converted into a lampas; this occurred in the consulship of Cn. Octavius and C. Scribonius.

It was seen by Silanus, the proconsul, and his attendants.

CHAP. 36. —OF STARS WHICH MOVE ABOUT IN VARIOUS DIRECTIONS.

Stars are seen to move about in various directions, but never without some cause, nor without violent winds proceeding from the same quarter.

CHAP. 37. —OF THE STARS WHICH ARE NAMED CASTOR AND POLLUX.

These stars occur both at sea and at land. I have seen, during the night-watches of the soldiers, a luminous appearance, like a star, attached to the javelins on the ramparts. They also settle on the yard-arms and other parts of ships while sailing, producing a kind of vocal sound, like that of birds flitting about. When they occur singly they are mischievous, so as even to sink the vessels, and if they strike on the lower part of the keel, setting them on fire. When there are two of them they are considered auspicious, and are thought to predict a prosperous voyage, as it is said that they drive away that dreadful and terrific meteor named Helena. On this account their efficacy is ascribed to Castor and Pollux, and they are invoked as gods. They also occasionally shine round the heads of men in the evening, which is considered as predicting something very important. But there is great uncertainty respecting the cause of all these things, and they are concealed in the majesty of nature.