Editors Note

This is Book II – Part III of the thirty seven books in Plinys’ Natural History. In order to make the collection more accessible and easier to navigate, most of the books have been divided into several parts. This book has been divided into six parts:

Part I – On God, the World, the Planets, the Sun and the Moon

Part II – On Stars and their characteristics, Meteors, Comets and Solar or Lunar Eclipses

Part III – On Seasons, Weather, Winds, Thunder and Lightning

Part IV – On Weather, the Earth, Climate and Daylight

Part V – On Earthquakes, Islands evolution, and Effects of the Sea on Land

Part VI – On the Sea, Fire, Dimensions of the Earth and the Universe

Translated by John Bostock MD, F.R.S (1773-1846) and Henry T. Riley Esq., B.A. (1816-1878), first published 1855. No changes have been made to the text, however all footnotes have been removed.

CHAP. 38. —OF THE AIR AND ON THE CAUSE OF THE SHOWERS OF STONES.

So far I have spoken of the world itself and of the stars. I must now give an account of the other remarkable phænomena of the heavens. For our ancestors have given the name of heavens, or, sometimes, another name, air, to all the seemingly void space, which diffuses around us this vital spirit. It is situated beneath the moon, indeed much lower, as is admitted by every one who has made observations on it, and is composed of a great quantity of air from the upper regions, mixed with a great quantity of terrestrial vapour, the two forming a compound. Hence proceed clouds, thunder and lightning of all kinds; hence also hail, frost, showers, storms and whirlwinds; hence proceed many of the evils incident to mortals, and the mutual contests of the various parts of nature. The force of the stars keeps down all terrestrial things which tend towards the heavens, and the same force attracts to itself those things which do not go there spontaneously. The showers fall, mists rise up, rivers are dried up, hail-storms rush down, the rays of the sun parch the earth, and impel it from all quarters towards the centre. The same rays, still unbroken, dart back again, and carry with them whatever they can take up. Vapour falls from on high and returns again to the same place. Winds arise which contain nothing, but which return loaded with spoils. The breathing of so many animals draws down the spirit from the higher regions; but this tends to go in a contrary direction, and the earth pours out its spirit into the void space of the heavens. Thus nature moving to and fro, as if impelled by some machine, discord is kindled by the rapid motion of the world. Nor is the contest allowed to cease, for she is continually whirled round and lays open the causes of all things, forming an immense globe about the earth, while she again, from time to time, covers this other firmament with clouds. This is the region of the winds. Here their nature principally originates, as well as the causes of almost all other things; since most persons ascribe the darting of thunder and lightning to their violence. And to the same cause are assigned the showers of stones, these having been previously taken up by the wind, as well as many other bodies in the same way. On this account we must enter more at large on this subject.

CHAP. 39. —OF THE STATED SEASONS.

It is obvious that there are causes of the seasons and of other things which have been stated, while there are some things which are casual, or of which the reason has not yet been discovered. For who can doubt that summer and winter, and the annual revolution of the seasons are caused by the motion of the stars? As therefore the nature of the sun is understood to influence the temperature of the year, so each of the other stars has its specific power, which produces its appropriate effects. Some abound in a fluid retaining its liquid state, others, in the same fluid concreted into hoar frost, compressed into snow, or frozen into hail; some are prolific in winds, some in heat, some in vapours, some in dew, some in cold. But these bodies must not be supposed to be actually of the size which they appear, since the consideration of their immense height clearly proves, that none of them are less than the moon. Each of them exercises its influence over us by its own motions; this is particularly observable with respect to Saturn, which produces a great quantity of rain in its transits. Nor is this power confined to the stars which change their situations, but is found to exist in many of the fixed stars, whenever they are impelled by the force of any of the planets, or excited by the impulse of their rays; as we find to be the case with respect to the Suculæ, which the Greeks, in reference to their rainy nature, have termed the Hyades. There are also certain events which occur spontaneously, and at stated periods, as the rising of the Kids. The star Arcturus scarcely ever rises without storms of hail occurring.

CHAP. 40. —OF THE RISING OF THE DOG-STAR.

Who is there that does not know that the vapour of the sun is kindled by the rising of the Dog-star? The most powerful effects are felt on the earth from this star. When it rises, the seas are troubled, the wines in our cellars ferment, and stagnant waters are set in motion. There is a wild beast, named by the Egyptians Oryx, which, when the star rises, is said to stand opposite to it, to look steadfastly at it, and then to sneeze, as if it were worshiping it. There is no doubt that dogs, during the whole of this period, are peculiarly disposed to become rabid.

CHAP. 41. —OF THE REGULAR INFLUENCE OF THE DIFFERENT SEASONS.

There is moreover a peculiar influence in the different degrees of certain signs, as in the autumnal equinox, and also in the winter solstice, when we find that a particular star is connected with the state of the weather. It is not so much the recurrence of showers and storms, as of various circumstances, which act both upon animals and vegetables. Some are planet-struck, and others, at stated times, are affected in the bowels, the sinews, the head, or the intellect.

The olive, the white poplar, and the willow turn their leaves round at the summer solstice. The herb pulegium, when dried and hanging up in a house, blossoms on the very day of the winter solstice, and bladders burst in consequence of their being distended with air. One might wonder at this, did we not observe every day, that the plant named heliotrope always looks towards the setting sun, and is, at all hours, turned towards him, even when he is obscured by clouds. It is certain that the bodies of oysters and of whelks, and of shell-fish generally, are increased in size and again diminished by the influence of the moon. Certain accurate observers have found out, that the entrails of the field-mouse correspond in number to the moon’s age, and that the very small animal, the ant, feels the power of this luminary, always resting from her labours at the change of the moon. And so much the more disgraceful is our ignorance, as every one acknowledges that the diseases in the eyes of certain beasts of burden increase and diminish according to the age of the moon. But the immensity of the heavens, divided as they are into seventy-two constellations, may serve as an excuse. These are the resemblances of certain things, animate and inanimate, into which the learned have divided the heavens. In these they have announced 1600 stars, as being remarkable either for their effects or their appearance; for example, in the tail of the Bull there are seven stars, which are named Vergiliæ; in his forehead are the Suculæ; there is also Bootes, which follows the seven northern stars.

CHAP. 42. —OF UNCERTAIN STATES OF THE WEATHER.

But I would not deny, that there may exist showers and winds, independent of these causes, since it is certain that an exhalation proceeds from the earth, which is sometimes moist, and at other times, in consequence of the vapours, like dense smoke; and also, that clouds are formed, either from the fluid rising up on high, or from the air being compressed into a fluid. Their density and their substance is very clearly proved from their intercepting the sun’s rays, which are visible by divers, even in the deepest waters.

CHAP. 43. —OF THUNDER AND LIGHTNING.

It cannot therefore be denied, that fire proceeding from the stars which are above the clouds, may fall on them, as we frequently observe on serene evenings, and that the air is agitated by the impulse, as darts when they are hurled whiz through the air. And when it arrives at the cloud, a discordant kind of vapour is produced, as when hot iron is plunged into water, and a wreath of smoke is evolved. Hence arise squalls. And if wind or vapour be struggling in the cloud, thunder is discharged; if it bursts out with a flame, there is a thunderbolt; if it be long in forcing out its way, it is simply a flash of lightning. By the latter the cloud is simply rent, by the former it is shattered. Thunder is produced by the stroke given to the condensed air, and hence it is that the fire darts from the chinks of the clouds. It is possible also that the vapour, which has risen from the earth, being repelled by the stars, may produce thunder, when it is pent up in a cloud; nature restraining the sound whilst the vapour is struggling to escape, but when it does escape, the sound bursting forth, as is the case with bladders that are distended with air. It is possible also that the spirit, whatever it be, may be kindled by friction, when it is so violently projected. It is possible that, by the dashing of the two clouds, the lightning may flash out, as is the case when two stones are struck against each other. But all these things appear to be casual. Hence there are thunderbolts which produce no effect, and proceed from no immediate actual cause; by these mountains and seas are struck, and no injury is done. Those which prognosticate future events proceed from on high and from stated causes, and they come from their peculiar stars.

CHAP. 44.—THE ORIGIN OF WINDS.

In like manner I would not deny that winds, or rather sudden gusts, are produced by the arid and dry vapours of the earth; that air may also be exhaled from water, which can neither be condensed into a mist, nor compressed into a cloud; that it may be also driven forward by the impulse of the sun, since by the term ‘wind’ we mean nothing more than a current of air, by whatever means it may be produced. For we observe winds to proceed from rivers and bays, and from the sea, even when it is tranquil; while others, which are named Altani, rise up from the earth; when they come back from the sea they are named Tropæi, but if they go straight on, Apogæi.

The windings and the numerous peaks of mountains, their ridges, bent into angles or broken into defiles, with the hollow valleys, by their irregular forms, cleaving the air which rebounds from them (which is also the cause why voices are, in many cases, repeated several times in succession), give rise to winds.

There are certain caves, such as that on the coast of Dalmatia, with a vast perpendicular chasm, into which, if a light weight only be let down, and although the day be calm, a squall issues from it like a whirlwind. The name of the place is Senta. And also, in the province of Cyrenaica, there is a certain rock, said to be sacred to the south wind, which it is profane for a human hand to touch, as the south wind immediately rolls forwards clouds of sand. There are also, in many houses, artificial cavities, formed in the walls, which produce currents of air; none of these are without their appropriate cause.

CHAP. 45.—VARIOUS OBSERVATIONS RESPECTING WINDS.

But there is a great difference between a gale and a wind. The former are uniform and appear to rush forth; they are felt, not in certain spots only, but over whole countries, not forming breezes or squalls, but violent storms. Whether they be produced by the constant revolution of the world and the opposite motion of the stars, or whether they both of them depend on the generative spirit of the nature of things, wandering, as it were, up and down in her womb, or whether the air be scourged by the irregular strokes of the wandering stars, or the various projections of their rays, or whether they, each of them, proceed from their own stars, among which are those that are nearest to us, or whether they descend from those that are fixed in the heavens, it is manifest that they are all governed by a law of nature, which is not altogether unknown, although it be not completely ascertained.

More than twenty old Greek writers have published their observations upon this subject. And this is the more remarkable, seeing that there is so much discord in the world, and that it is divided into different kingdoms, that is into separate members, that there should have been so many who have paid attention to these subjects, which are so difficult to investigate. Especially when we consider the wars and the treachery which everywhere prevail; while pirates, the enemies of the human race, have possession of all the modes of communication, so that, at this time, a person may acquire more correct information about a country from the writings of those who have never been there, than from the inhabitants themselves. Whereas, at this day, in the blessed peace which we enjoy, under a prince who so greatly encourages the advancement of the arts, no new inquiries are set on foot, nor do we even make ourselves thoroughly masters of the discoveries of the ancients. Not that there were greater rewards held out, from the advantages being distributed to a greater number of persons, but that there were more individuals who diligently scrutinized these matters, with no other prospect but that of benefiting posterity. It is that the manners of men are degenerated, not that the advantages are diminished. All the seas, as many as there are, being laid open, and a hospitable reception being given us at every shore, an immense number of people undertake voyages; but it is for the sake of gain, not of science. Nor does their understanding, which is blinded and bent only on avarice, perceive that this very thing might be more safely done by means of science. Seeing, therefore, that there are so many thousands of persons on the seas, I will treat of the winds with more minuteness than perhaps might otherwise appear suitable to my undertaking.

CHAP. 46. —THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF WINDS.

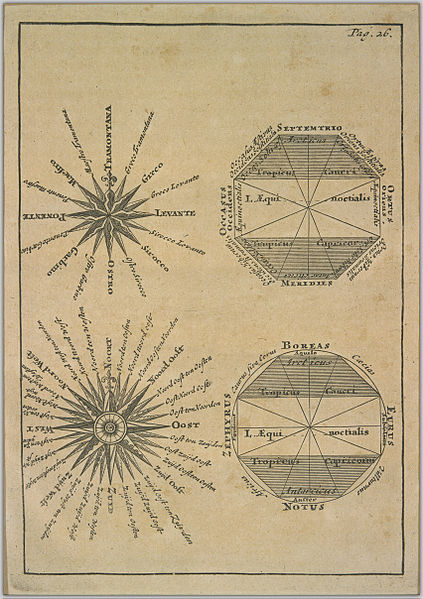

The ancients reckoned only four winds (nor indeed does Homer mention more) corresponding to the four parts of the world; a very poor reason, as we now consider it. The next generation added eight others, but this was too refined and minute a division; the moderns have taken a middle course, and, out of this great number, have added four to the original set. There are, therefore, two in each of the four quarters of the heavens. From the equinoctial rising of the sun proceeds Subsolanus, and, from his brumal rising, Vulturnus; the former is named by the Greeks Apeliotes, the latter Eurus. From the south we have Auster, and from the brumal setting of the sun, Africus; these were named Notos and Libs. From the equinoctial setting proceeds Favonius, and from the solstitial setting, Corus; these were named Zephyrus and Argestes. From the seven stars comes Septemtrio, between which and the solstitial rising we have Aquilo, named Aparctias and Boreas. By a more minute subdivision we interpose four others, Thrascias, between Septemtrio and the solstitial setting; Cæcias, between Aquilo and the equinoctial rising; and Phœnices, between the brumal rising and the south. And also, at an equal distance from the south and the winter setting, between Libs and Notos, and compounded of the two, is Libonotos. Nor is this all. For some persons have added a wind, which they have named Meses, between Boreas and Cæcias, and one between Eurus and Notos, named Euronotus.

There are also certain winds peculiar to certain countries, which do not extend beyond certain districts, as Sciron in Attica, deviating a little from Argestes, and not known in the other parts of Greece. In other places it is a little higher on the card and is named Olympias; but all these have gone by the name of Argestes. In some places Cæcias is named Hellespontia, and the same is done in other cases. In the province of Narbonne the most noted wind is Circius; it is not inferior to any of the winds in violence, frequently driving the waves before it, to Ostia, straight across the Ligurian sea. Yet this same wind is unknown in other parts, not even reaching Vienne, a city in the same province; for meeting with a high ridge of hills, just before it arrives at that district, it is checked, although it be the most violent of all the winds. Fabius also asserts, that the south winds never penetrate into Egypt. Hence this law of nature is obvious, that winds have their stated seasons and limits.

CHAP. 47.—THE PERIODS OF THE WINDS.

The spring opens the seas for the navigators. In the beginning of this season the west winds soften, as it were, the winter sky, the sun having now gained the 25th degree of Aquarius; this is on the sixth day before the Ides of February. This agrees, for the most part, with all the remarks that I shall subsequently make, only anticipating the period by one day in the intercalary year, and again, preserving the same order in the succeeding lustrum. After the eighth day before the Calends of March, Favonius is called by some Chelidonias, from the swallows making their appearance. The wind, which blows for the space of nine days, from the seventy-first day after the winter solstice, is sometimes called Ornithias, from the arrival of the birds. In the contrary direction to Favonius is the wind which we name Subsolanus, and this is connected with the rising of the Vergiliæ, in the 25th degree of Taurus, six days before the Ides of May, which is the time when south winds prevail: these are opposite to Septemtrio. The dog-star rises in the hottest time of the summer, when the sun is entering the first degree of Leo; this is fifteen days before the Calends of August. The north winds, which are called Prodromi, precede its rising by about eight days. But in two days after its rising, the same north winds, which are named Etesiæ, blow more constantly during this period; the vapour from the sun, being increased twofold by the heat of this star, is supposed to render these winds more mild; nor are there any which are more regular. After these the south winds become more frequent, until the appearance of Arcturus, which rises eleven days before the autumnal equinox. At this time Corus sets in; Corus is an autumnal wind, and is in the opposite direction to Vulturnus. After this, and generally for forty-four days after the equinox, at the setting of the Vergiliæ, the winter commences, which usually happens on the third of the Ides of November. This is the period of the winter north wind, which is very unlike the summer north wind, and which is in the opposite direction to Africus. For seven days before the winter solstice, and for the same length of time after it, the sea becomes calm, in order that the king-fishers may rear their young; from this circumstance they have obtained the name of the halcyon days; the rest of the season is winterly. Yet the severity of the storms does not entirely close up the sea. In former times, pirates were compelled, by the fear of death, to rush into death, and to brave the winter ocean; now we are driven to it by avarice.

CHAP. 48.—NATURE OF THE WINDS.

Those are the coldest winds which are said to blow from the seven stars, and Corus, which is contiguous to them; these also restrain the others and dispel the clouds. The moist winds are Africus, and, still more, the Auster of Italy. It is said that, in Pontus, Cæcias attracts the clouds. The dry winds are Corus and Vulturnus, especially when they are about to cease blowing. The winds that bring snow are Aquilo and Septemtrio; Septemtrio brings hail, and so does Corus; Auster is sultry, Vulturnus and Zephyrus are warm. These winds are more dry than Subsolanus, and generally those which blow from the north and west are more dry than those which blow from the south and east. Aquilo is the most healthy of them all; Auster is unhealthy, and more so when dry; it is colder, perhaps because it is moist. Animals are supposed to have less appetite for food when this wind is blowing. The Etesiæ generally cease during the night, and spring up at the third hour of the day. In Spain and in Asia these winds have an easterly direction, in Pontus a northerly, and in other places a southerly direction. They blow also after the winter solstice, when they are called Ornithiæ, but they are more gentle and continue only for a few days. There are two winds which change their nature with their situation; in Africa Auster is attended with a clear sky, while Aquilo collects the clouds. Almost all winds blow in their turn, so that when one ceases its opposite springs up. When winds which are contiguous succeed each other, they go from left to right, in the direction of the sun. The fourth day of the moon generally determines their direction for the whole of the monthly period. We are able to sail in opposite directions by means of the same wind, if we have the sails properly set; hence it frequently happens that, in the night, vessels going in different directions run against each other. Auster produces higher winds than Aquilo, because the former blows, as it were, from the bottom of the sea, while the latter blows on the surface; it is therefore after south winds that the most mischievous earthquakes have occurred. Auster is more violent during the night, Aquilo during the day; winds from the east continue longer than from the west. The north winds generally cease blowing on the odd days, and we observe the prevalence of the odd numbers in many other parts of nature; the male winds are therefore regulated by the odd numbers. The sun sometimes increases and sometimes restrains winds; when rising and setting it increases them; while, when on the meridian, it restrains them during the summer. They are, therefore, generally lulled during the middle of the day and of the night, because they are abated either by excessive cold or heat; winds are also lulled by showers. We generally expect them to come from that quarter where the clouds open and allow the clear sky to be seen. Eudoxus supposes that the same succession of changes occurs in them after a period of four years, if we observe their minute revolutions; and this applies not only to winds, but to whatever concerns the state of the weather. He begins his lustrum at the rising of the dog-star, in the intercalary year. So far concerning winds in general.

CHAP. 49. —ECNEPHIAS AND TYPHON.

And now respecting the sudden gusts, which arising from the exhalations of the earth, as has been said above, and falling down again, being in the mean time covered by a thin film of clouds, exist in a variety of forms. By their wandering about, and rushing down like torrents, in the opinion of some persons, they produce thunder and lightning. But if they be urged on with greater force and violence, so as to cause the rupture of a dry cloud, they produce a squall, which is named by the Greeks Ecnephias. But, if these are compressed, and rolled up more closely together, and then break without any discharge of fire, i. e. without thunder, they produce a squall, which is named Typhon, or an Ecnephias in a state of agitation. It carries along a portion of the cloud which it has broken off, rolling it and turning it round, aggravating its own destruction by the weight of it, and whirling it from place to place. This is very much dreaded by sailors, as it not only breaks their sail-yards, but the vessels themselves, bending them about in various ways. This may be in a slight degree counteracted by sprinkling it with vinegar, when it comes near us, this substance being of a very cold nature. This wind, when it rebounds after the stroke, absorbs and carries up whatever it may have seized on.

CHAP. 50.—TORNADOES; BLASTING WINDS; WHIRLWINDS, AND OTHER WONDERFUL KINDS OF TEMPESTS.

But if it burst from the cavity of a cloud which is more depressed, but less capacious than what produces a squall, and is accompanied by noise, it is called a whirlwind, and throws down everything which is near it. The same, when it is more burning and rages with greater heat, is called a blasting wind, scorching and, at the same time, throwing down everything with which it comes in contact. Typhon never comes from the north, nor have we Ecnephias when it snows, or when there is snow on the ground. If it breaks the clouds, and, at the same time, catches fire or burns, but not until it has left the cloud, it forms a thunder-bolt. It differs from Prester as flame does from fire; the former is diffused in a gust, the latter is condensed with a violent impulse. The whirlwind, when it rebounds, differs from the tornado in the same manner as a loud noise does from a dash.

The squall differs from both of them in its extent, the clouds being more properly rent asunder than broken into pieces. A black cloud is formed, resembling a great animal, an appearance much dreaded by sailors. It is also called a pillar, when the moisture is so condensed and rigid as to be able to support itself. It is a cloud of the same kind, which, when drawn into a tube, sucks up the water.

CHAP. 51. —OF THUNDER; IN WHAT COUNTRIES IT DOES NOT FALL, AND FOR WHAT REASON.

Thunder is rare both in winter and in summer, but from different causes; the air, which is condensed in the winter, is made still more dense by a thicker covering of clouds, while the exhalations from the earth, being all of them rigid and frozen, extinguish whatever fiery vapour it may receive. It is this cause which exempts Scythia and the cold districts round it from thunder. On the other hand, the excessive heat exempts Egypt; the warm and dry vapours of the earth being very seldom condensed, and that only into light clouds. But, in the spring and autumn, thunder is more frequent, the causes which produce summer and winter being, in each season, less efficient. From this cause thunder is more frequent in Italy, the air being more easily set in motion, in consequence of a milder winter and a showery summer, so that it may be said to be always spring or autumn. Also in those parts of Italy which recede from the north and lie towards the south, as in the district round our city, and in Campania, it lightens equally both in winter and in summer, which is not the case in other situations.

CHAP. 52. —OF THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF LIGHTNING AND THEIR WONDERFUL EFFECTS.

We have accounts of many different kinds of thunder-storms. Those which are dry do not burn objects, but dissipate them; while those which are moist do not burn, but blacken them. There is a third kind, which is called bright lightning, of a very wonderful nature, by which casks are emptied, without the vessels themselves being injured, or there being any other trace left of their operation. Gold, copper, and silver are melted, while the bags which contain them are not in the least burned, nor even the wax seal much defaced. Marcia, a lady of high rank at Rome, was struck while pregnant; the fœtus was destroyed, while she herself survived without suffering any injury. Among the prognostics which took place at the time of Catiline’s conspiracy, M. Herennius, a magistrate of the borough of Pompeii, was struck by lightning when the sky was without clouds.

CHAP. 53. —THE ETRURIAN AND THE ROMAN OBSERVATIONS ON THESE POINTS.

The Tuscan books inform us, that there are nine Gods who discharge thunder-storms, that there are eleven different kinds of them, and that three of them are darted out by Jupiter. Of these the Romans retained only two, ascribing the diurnal kind to Jupiter, and the nocturnal to Summanus; this latter kind being more rare, in consequence of the heavens being colder, as was mentioned above. The Etrurians also suppose, that those which are named Infernal burst out of the ground; they are produced in the winter and are particularly fierce and direful, as all things are which proceed from the earth, and are not generated by or proceeding from the stars, but from a cause which is near at hand, and of a more disorderly nature. As a proof of this it is said, that all those which proceed from the higher regions strike obliquely, while those which are termed terrestrial strike in a direct line. And because these fall from matter which is nearer to us, they are supposed to proceed from the earth, since they leave no traces of a rebound; this being the effect of a stroke coming not from below, but from an opposite quarter. Those who have searched into the subject more minutely suppose, that these come from the planet Saturn, as those that are of a burning nature do from Mars. In this way it was that Volsinium, the most opulent town of the Tuscans, was entirely consumed by lightning. The first of these strokes that a man receives, after he has come into possession of any property, is termed Familiar, and is supposed to prognosticate the events of the whole of his life. But it is not generally supposed that they predict events of a private nature for a longer space than ten years, unless they happen at the time of a first marriage or a birth-day; nor that public predictions extend beyond thirty years, unless with respect to the founding of colonies.

CHAP. 54. —OF CONJURING UP THUNDER.

It is related in our Annals, that by certain sacred rites and imprecations, thunder-storms may be compelled or invoked. There is an old report in Etruria, that thunder was invoked when the city of Volsinium had its territory laid waste by a monster named Volta. Thunder was also invoked by King Porsenna. And L. Piso, a very respectable author, states in the first book of his Annals, that this had been frequently done before his time by Numa, and that Tullus Hostilius, imitating him, but not having properly performed the ceremonies, was struck with the lightning. We have also groves, and altars, and sacred places, and, among the titles of Jupiter, as Stator, Tonans, and Feretrius, we have a Jupiter Elicius. The opinions entertained on this point are very various, and depend much on the dispositions of different individuals. To believe that we can command nature is the mark of a bold mind, nor is it less the mark of a feeble one to reject her kindness. Our knowledge has been so far useful to us in the interpretation of thunder, that it enables us to predict what is to happen on a certain day, and we learn either that our fortune is to be entirely changed, or it discloses events which are concealed from us; as is proved by an infinite number of examples, public and private. Wherefore let these things remain, according to the order of nature, to some persons certain, to others doubtful, by some approved, by others condemned. I must not, however, omit the other circumstances connected with them which deserve to be related.

CHAP. 55. —GENERAL LAWS OF LIGHTNING.

It is certain that the lightning is seen before the thunder is heard, although they both take place at the same time. Nor is this wonderful, since light has a greater velocity than sound. Nature so regulates it, that the stroke and the sound coincide; the sound is, however, produced by the discharge of the thunder, not by its stroke. But the air is impelled quicker than the lightning, on which account it is that everything is shaken and blown up before it is struck, and that a person is never injured when he has seen the lightning and heard the thunder. Thunder on the left hand is supposed to be lucky, because the east is on the left side of the heavens. We do not regard so much the mode in which it comes to us, as that in which it leaves us, whether the fire rebounds after the stroke, or whether the current of air returns when the operation is concluded and the fire is consumed. In relation to this object the Etrurians have divided the heavens into sixteen parts. The first great division is from north to east; the second to the south; the third to the west, and the fourth occupies what remains from west to north. Each of these has been subdivided into four parts, of which the eight on the east have been called the left, and those on the west the right divisions. Those which extend from the west to the north have been considered the most unpropitious. It becomes therefore very important to ascertain from what quarter the thunder proceeds, and in what direction it falls. It is considered a very favourable omen when it returns into the eastern divisions. But it prognosticates the greatest felicity when the thunder proceeds from the first-mentioned part of the heavens and falls back into it; it was an omen of this kind which, as we have heard, was given to Sylla, the Dictator. The remaining quarters of the heavens are less propitious, and also less to be dreaded. There are some kinds of thunder which it is not thought right to speak of, or even to listen to, unless when they have been disclosed to the master of a family or to a parent. But the futility of this observation was detected when the temple of Juno was struck at Rome, during the consulship of Scaurus, he who was afterwards the Prince of the Senate.

It lightens without thunder more frequently in the night than in the day. Man is the only animal that is not always killed by it, all other animals being killed instantly, nature having granted to him this mark of distinction, while so many other animals excel him in strength. All animals fall down on the opposite side to that which has been struck; man, unless he be thrown down on the parts that are struck, does not expire. Those who are struck directly from above sink down immediately. When a man is struck while he is awake, he is found with his eyes closed; when asleep, with them open. It is not considered proper that a man killed in this way should be burnt on the funeral pile; our religion enjoins us to bury the body in the earth. No animal is consumed by lightning unless after having been previously killed. The parts of the animal that have been wounded by lightning are colder than the rest of the body.

CHAP. 56. —OBJECTS WHICH ARE NEVER STRUCK.

Among the productions of the earth, thunder never strikes the laurel, nor does it descend more than five feet into the earth. Those, therefore, who are timid consider the deepest caves as the most safe; or tents made of the skins of the animal called the sea-calf, since this is the only marine animal which is never struck; as is the case, among birds, with the eagle; on this account it is represented as the bearer of this weapon. In Italy, between Terracina and the temple of Feronia, the people have left off building towers in time of war, every one of them having been destroyed by thunderbolts.

CHAP. 57. —SHOWERS OF MILK, BLOOD, FLESH, IRON, WOOL, AND BAKED TILES.

Besides these, we learn from certain monuments, that from the lower part of the atmosphere it rained milk and blood, in the consulship of M’ Acilius and C. Porcius, and frequently at other times. This was the case with respect to flesh, in the consulship of P. Volumnius and Servius Sulpicius, and it is said, that what was not devoured by the birds did not become putrid. It also rained iron among the Lucanians, the year before Crassus was slain by the Parthians, as well as all the Lucanian soldiers, of whom there was a great number in this army. The substance which fell had very much the appearance of sponge; the augurs warned the people against wounds that might come from above. In the consulship of L. Paulus and C. Marcellus it rained wool, round the castle of Carissanum, near which place, a year after, T. Annius Milo was killed. It is recorded, among the transactions of that year, that when he was pleading his own cause, there was a shower of baked tiles.

CHAP. 58. —RATTLING OF ARMS AND THE SOUND OF TRUMPETS HEARD IN THE SKY.

We have heard, that during the war with the Cimbri, the rattling of arms and the sound of trumpets were heard through the sky, and that the same thing has frequently happened before and since. Also, that in the third consulship of Marius, armies were seen in the heavens by the Amerini and the Tudertes, encountering each other, as if from the east and west, and that those from the east were repelled. It is not at all wonderful for the heavens themselves to be in flames, and it has been more frequently observed when the clouds have taken up a great deal of fire.

CHAP. 59. —OF STONES THAT HAVE FALLEN FROM THE CLOUDS. THE OPINION OF ANAXAGORAS RESPECTING THEM.

The Greeks boast that Anaxagoras, the Clazomenian, in the second year of the 78th Olympiad, from his knowledge of what relates to the heavens, had predicted, that at a certain time, a stone would fall from the sun. And the thing accordingly happened, in the daytime, in a part of Thrace, at the river Ægos. The stone is now to be seen, a waggon-load in size and of a burnt appearance; there was also a comet shining in the night at that time. But to believe that this had been predicted would be to admit that the divining powers of Anaxagoras were still more wonderful, and that our knowledge of the nature of things, and indeed every thing else, would be thrown into confusion, were we to suppose either that the sun is itself composed of stone, or that there was even a stone in it; yet there can be no doubt that stones have frequently fallen from the atmosphere. There is a stone, a small one indeed, at this time, in the Gymnasium of Abydos, which on this account is held in veneration, and which the same Anaxagoras predicted would fall in the middle of the earth. There is another at Cassandria, formerly called Potidæa, which from this circumstance was built in that place. I have myself seen one in the country of the Vocontii, which had been brought from the fields only a short time before.

Featured Image Credit: Douce Pliny 1476, Public Domain in the USA.