Editors Note

This is Book II – Part VI of the thirty seven books in Plinys’ Natural History. In order to make the collection more accessible and easier to navigate, most of the books have been divided into several parts. This book has been divided into six parts:

Part I – On God, the World, the Planets, the Sun and the Moon

Part II – On Stars and their characteristics, Meteors, Comets and Solar or Lunar Eclipses

Part III – On Seasons, Weather, Winds, Thunder and Lightning

Part IV – On Weather, the Earth, Climate and Daylight

Part V – On Earthquakes, Islands evolution, and Effects of the Sea on Land

Part VI – On the Sea, Fire, Dimensions of the Earth and the Universe

Translated by John Bostock MD, F.R.S (1773-1846) and Henry T. Riley Esq., B.A. (1816-1878), first published 1855. No changes have been made to the text, however all footnotes have been removed.

CHAP. 97. —PLACES IN WHICH IT NEVER RAINS.

There is at Paphos a celebrated temple of Venus, in a certain court of which it never rains; also at Nea, a town of Troas, in the spot which surrounds the statue of Minerva: in this place also the remains of animals that are sacrificed never putrefy.

CHAP. 98.—THE WONDERS OF VARIOUS COUNTRIES COLLECTED TOGETHER.

Near Harpasa, a town of Asia, there stands a terrific rock, which may be moved by a single finger; but if it be pushed by the force of the whole body, it resists. In the Tauric peninsula, in the state of the Parasini, there is a kind of earth which cures all wounds. About Assos, in Troas, a stone is found, by which all bodies are consumed; it is called Sarcophagus. There are two mountains near the river Indus; the nature of one is to attract iron, of the other to repel it: hence, if there be nails in the shoes, the feet cannot be drawn off the one, or set down on the other. It has been noticed, that at Locris and Crotona, there has never been a pestilence, nor have they ever suffered from an earthquake; in Lycia there are always forty calm days before an earthquake. In the territory of Argyripa the corn which is sown never springs up. At the altars of Mucius, in the country of the Veii, and about Tusculum, and in the Cimmerian Forest, there are places in which things that are pushed into the ground cannot be pulled out again. The hay which is grown in Crustuminium is noxious on the spot, but elsewhere it is wholesome.

CHAP. 99. —CONCERNING THE CAUSE OF THE FLOWING AND EBBING OF THE SEA.

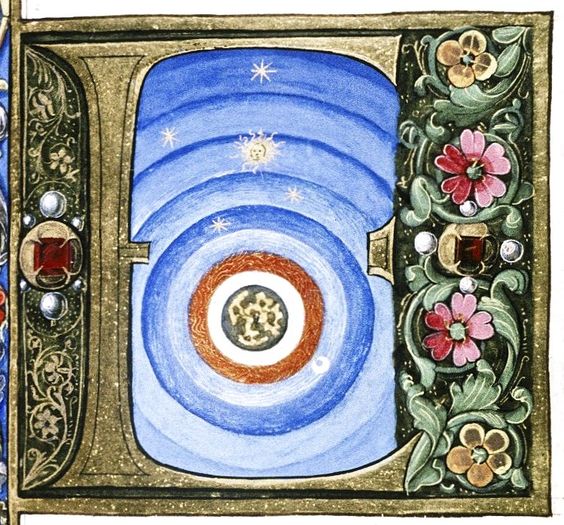

Much has been said about the nature of waters; but the most wonderful circumstance is the alternate flowing and ebbing of the tides, which exists, indeed, under various forms, but is caused by the sun and the moon. The tide flows twice and ebbs twice between each two risings of the moon, always in the space of twenty-four hours. First, the moon rising with the stars swells out the tide, and after some time, having gained the summit of the heavens, she declines from the meridian and sets, and the tide subsides. Again, after she has set, and moves in the heavens under the earth, as she approaches the meridian on the opposite side, the tide flows in; after which it recedes until she again rises to us. But the tide of the next day is never at the same time with that of the preceding; as if the planet was in attendance, greedily drinking up the sea, and continually rising in a different place from what she did the day before. The intervals are, however, equal, being always of six hours; not indeed in respect of any particular day or night or place, but equinoctial hours, and therefore they are unequal as estimated by the length of common hours, since a greater number of them fall on some certain days or nights, and they are never equal everywhere except at the equinox. This is a great, most clear, and even divine proof of the dullness of those, who deny that the stars go below the earth and rise up again, and that nature presents the same face in the same states of their rising and setting; for the course of the stars is equally obvious in the one case as in the other, producing the same effect as when it is manifest to the sight.

There is a difference in the tides, depending on the moon, of a complicated nature, and, first, as to the period of seven days. For the tides are of moderate height from the new moon to the first quarter; from this time they increase, and are the highest at the full: they then decrease. On the seventh day they are equal to what they were at the first quarter, and they again increase from the time that she is at first quarter on the other side. At her conjunction with the sun they are equally high as at the full. When the moon is in the northern hemisphere, and recedes further from the earth, the tides are lower than when, going towards the south, she exercises her influence at a less distance. After an interval of eight years, and the hundredth revolution of the moon, the periods and the heights of the tides return into the same order as at first, this planet always acting upon them; and all these effects are likewise increased by the annual changes of the sun, the tides rising up higher at the equinoxes, and more so at the autumnal than at the vernal; while they are lower about the winter solstice, and still more so at the summer solstice; not indeed precisely at the points of time which I have mentioned, but a few days after; for example, not exactly at the full nor at the new moon, but after them; and not immediately when the moon becomes visible or invisible, or has advanced to the middle of her course, but generally about two hours later than the equinoctial hours; the effect of what is going on in the heavens being felt after a short interval; as we observe with respect to lightning, thunder, and thunderbolts.

But the tides of the ocean cover greater spaces and produce greater inundations than the tides of the other seas; whether it be that the whole of the universe taken together is more full of life than its individual parts, or that the large open space feels more sensibly the power of the planet, as it moves freely about, than when restrained within narrow bounds.

On which account neither lakes nor rivers are moved in the same manner. Pytheas of Massilia informs us, that in Britain the tide rises 80 cubits. Inland seas are enclosed as in a harbour, but, in some parts of them, there is a more free space which obeys the influence. Among many other examples, the force of the tide will carry us in three days from Italy to Utica, when the sea is tranquil and there is no impulse from the sails. But these motions are more felt about the shores than in the deep parts of the seas, as in the body the extremities of the veins feel the pulse, which is the vital spirit, more than the other parts. And in most estuaries, on account of the unequal rising of the stars in each tract, the tides differ from each other, but this respects the period, not the nature of them; as is the case in the Syrtes.

CHAP. 100.—WHERE THE TIDES RISE AND FALL IN AN UNUSUAL MANNER.

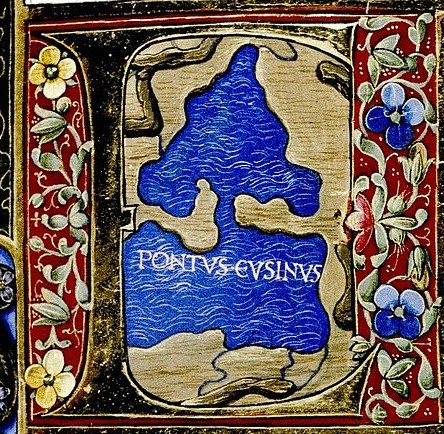

There are, however, some tides which are of a peculiar nature, as in the Tauromenian Euripus, where the ebb and flow is more frequent than in other places, and in Eubœa, where it takes place seven times during the day and the night. The tides intermit three times during each month, being the 7th, 8th and 9th day of the moon. At Gades, which is very near the temple of Hercules, there is a spring enclosed like a well, which sometimes rises and falls with the ocean, and, at other times, in both respects contrary to it. In the same place there is another well, which always agrees with the ocean. On the shores of the Bætis, there is a town where the wells become lower when the tide rises, and fill again when it ebbs; while at other times they remain stationary. The same thing occurs in one well in the town of Hispalis, while there is nothing peculiar in the other wells. The Euxine always flows into the Propontis, the water never flowing back into the Euxine.

CHAP. 101. —WONDERS OF THE SEA.

All seas are purified at the full moon; some also at stated periods. At Messina and Mylæ a refuse matter, like dung, is cast up on the shore, whence originated the story of the oxen of the Sun having had their stable at that place. To what has been said above (not to omit anything with which I am acquainted) Aristotle adds, that no animal dies except when the tide is ebbing. The observation has been often made on the ocean of Gaul; but it has only been found true with respect to man.

CHAP. 102. —THE POWER OF THE MOON OVER THE LAND AND THE SEA.

Hence we may certainly conjecture, that the moon is not unjustly regarded as the star of our life. This it is that replenishes the earth; when she approaches it, she fills all bodies, while, when she recedes, she empties them. From this cause it is that shell-fish grow with her increase, and that those animals which are without blood more particularly experience her influence; also, that the blood of man is increased or diminished in proportion to the quantity of her light; also that the leaves and vegetables generally, as I shall describe in the proper place, feel her influence, her power penetrating all things.

CHAP. 103. —THE POWER OF THE SUN.

Fluids are dried up by the heat of the sun; we have therefore regarded it as a masculine star, burning up and absorbing everything.

CHAP. 104.—WHY THE SEA IS SALT.

Hence it is that the widely-diffused sea is impregnated with the flavour of salt, in consequence of what is sweet and mild being evaporated from it, which the force of fire easily accomplishes; while all the more acrid and thick matter is left behind; on which account the water of the sea is less salt at some depth than at the surface. And this is a more true cause of the acrid flavour, than that the sea is the continued perspiration of the land, or that the greater part of the dry vapour is mixed with it, or that the nature of the earth is such that it impregnates the waters, and, as it were, medicates them. Among the prodigies which have occurred, there is one which happened when Dionysius, the tyrant of Sicily, was expelled from his kingdom; that, for the space of one day, the water in the harbour became sweet.

The moon, on the contrary, is said to be a feminine and delicate planet, and also nocturnal; also that it resolves humours and draws them out, but does not carry them off. It is manifest that the carcases of wild beasts are rendered putrid by its beams, that, during sleep, it draws up the accumulated torpor into the head, that it melts ice, and relaxes all things by its moistening spirit. Thus the changes of nature compensate each other, and are always adequate to their destined purpose; some of them congealing the elements of the stars and others dissolving them. The moon is said to be fed by fresh, and the sun by salt water.

CHAP. 105. —WHERE THE SEA IS THE DEEPEST.

Fabianus informs us that the greatest depth of the sea is 15 stadia. We learn from others, that in the Euxine, opposite to the nation of the Coraxi, at what is called the Depths of the Euxine, about 300 stadia from the main land, the sea is immensely deep, no bottom having been found.

CHAP. 106. —THE WONDERS OF FOUNTAINS AND RIVERS.

It is very remarkable that fresh water should burst out close to the sea, as from pipes. But there is no end to the wonders that are connected with the nature of waters. Fresh water floats on sea water, no doubt from its being lighter; and therefore sea water, which is of a heavier nature, supports better what floats upon it. And, in some places, different kinds of fresh water float upon each other; as that of the river which falls into the Fucinus; that of the Addua into the Larius; of the Ticinus into the Verbanus; of the Mincius into the Benacus; of the Ollius into the Sevinus; and of the Rhone into the Leman lake (this last being beyond the Alps, the others in Italy): all which rivers passing through the lakes for many miles, generally carry off no more water than they bring with them. The same thing is said to occur in the Orontes, a river of Syria, and in many others.

Some rivers, from a real hatred of the sea, pass under it, as does Arethusa, a fountain of Syracuse, in which the substances are found that are thrown into the Alpheus; which, after flowing by Olympia, is discharged into the sea, on the shore of the Peloponnesus. The Lycus in Asia, the Erasinus in Argolis, and the Tigris in Mesopotamia, sink into the earth and burst out again. Substances which are thrown into the fountain of Æsculapius at Athens are cast up at the fountain of Phalerum. The river which sinks into the ground in the plain of Atinum comes up again at the distance of twenty miles, and the Timavus does the same in Aquileia.

In the lake Asphaltites, in Judæa, which produces bitumen, no substance will sink, nor in the lake Arethusa, in the Greater Armenia: in this lake, although it contains nitre, fish are found. In the country of the Salentini, near the town of Manduria, there is a lake full to the brim, the waters of which are never diminished by what is taken out of it, nor increased by what is added. Wood, which is thrown into the river of the Cicones, or into the lake Velinus in Picenum, becomes coated with a stony crust, while in the Surius, a river of Colchis, the whole substance becomes as hard as stone. In the same manner, in the Silarus, beyond Surrentum, not only twigs which are immersed in it, but likewise leaves are petrified; the water at the same time being proper for drinking. In the stream which runs from the marsh of Reate there is a rock, which continues to increase in size, and in the Red Sea olive-trees and green shrubs are produced.

There are many springs which are remarkable for their warmth. This is the case even among the ridges of the Alps, and in the sea itself, between Italy and Ænaria, as in the bay of Baiæ, and in the Liris and many other rivers. There are many places in which fresh water may be procured from the sea, as at the Chelidonian Isles, and at Arados, and in the ocean at Gades. Green plants are produced in the warm springs of Padua, frogs in those of Pisa, and fish in those of Vetulonia in Etruria, which is not far from the sea. In Casinas there is a cold river called Scatebra, which in summer is more full of water. In this, as in the river Stymphalis, in Arcadia, small water-mice are produced. The fountain of Jupiter in Dodona, although it is as cold as ice, and extinguishes torches that are plunged into it, yet, if they be brought near it, it kindles them again. This spring always becomes dry at noon, from which circumstance it is called Ἀναπαυόμενον: it then increases and becomes full at midnight, after which it again visibly decreases. In Illyricum there is a cold spring, over which if garments are spread they take fire. The pool of Jupiter Ammon, which is cold during the day, is warm during the night. In the country of the Troglodytæ, what they call the Fountain of the Sun, about noon is fresh and very cold; it then gradually grows warm, and, at midnight, becomes hot and saline.

In the middle of the day, during summer, the source of the Po, as if reposing itself, is always dry. In the island of Tenedos there is a spring, which, after the summer solstice, is full of water, from the third hour of the night to the sixth. The fountain Inopus, in the island of Delos, decreases and increases in the same manner as the Nile, and also at the same periods. There is a small island in the sea, opposite to the river Timavus, containing warm springs, which increase and decrease at the same time with the tides of the sea. In the territory of Pitinum, on the other side of the Apennines, the river Novanus, which during the solstice is quite a torrent, is dry in the winter.

In Faliscum, all the water which the oxen drink turns them white; in Bœotia, the river Melas turns the sheep black; the Cephissus, which flows out of a lake of the same name, turns them white; again, the Peneus turns them black, and the Xanthus, near Ilium, makes them red, whence the river derives its name. In Pontus, the river Astaces waters certain plains, where the mares give black milk, which the people use in diet. In Reate there is a spring called Neminia, which rises up sometimes in one place and sometimes in another, and in this way indicates a change in the produce of the earth. There is a spring in the harbour of Brundisium that yields water which never becomes putrid at sea. The water of the Lyncestis, which is said to be acidulous, intoxicates like wine; this is the case also in Paphlagonia and in the territory of Calenum. In the island of Andros, at the temple of Father Bacchus, we are assured by Mucianus, who was thrice consul, that there is a spring, which, on the nones of January, always has the flavour of wine; it is called Διὸς Θεοδοσία. Near Nonacris, in Arcadia, the Styx, which is not unlike it either in odour or in colour, instantly destroys those who drink it. Also in Librosus, a hill in the country of the Tauri, there are three springs which inevitably produce death, but without pain. In the territory of the Carrinenses in Spain, two springs burst out close together, the one of which absorbs everything, the other throws them out. In the same country there is another spring, which gives to all the fish the appearance of gold, although, when out of the water, they do not differ in any respect from other fish. In the territory of Como, near the Larian lake, there is a copious spring, which always swells up and subsides again every hour. In the island of Cydonea, before Lesbos, there is a warm fountain, which flows only during the spring season. The lake Sinnaus, in Asia, is impregnated with wormwood, which grows about it. At Colophon, in the cave of the Clarian Apollo, there is a pool, by the drinking of which a power is acquired of uttering wonderful oracles; but the lives of those who drink of it are shortened. In our own times, during the last years of Nero’s life, we have seen rivers flowing backwards, as I have stated in my history of his times.

And indeed who can be mistaken as to the fact, that all springs are colder in summer than in winter, as well as these other wonderful operations of nature; that copper and lead sink when in a mass, but float when spread out; and of things that are equally heavy, some will sink to the bottom, while others will remain on the surface; that heavy bodies are more easily moved in water; that a stone from Scyros, although very large, will float, while the same, when broken into small pieces, sinks; that the body of an animal, newly deprived of life, sinks, but that, when it is swelled out, it floats; that empty vessels are drawn out of the water with no more ease than those that are full; that rain-water is more useful for salt-pits than other kinds of water; that salt cannot be made, unless it is mixed with fresh water; that salt water freezes with more difficulty, and is more readily heated; that the sea is warmer in winter and more salt in the autumn; that everything is soothed by oil, and that this is the reason why divers send out small quantities of it from their mouths, because it smoothes any part which is rough and transmits the light to them; that snow never falls in the deep part of the sea; that although water generally has a tendency downwards, fountains rise up, and that this is the case even at the foot of Ætna, burning as it does, so as to force out the sand like a ball of flame to the distance of 150 miles?

CHAP. 107.—THE WONDERS OF FIRE AND WATER UNITED.

And now I must give an account of some of the wonders of fire, which is the fourth element of nature; but first those produced by means of water.

CHAP. 108. —OF MALTHA.

In Samosata, a city of Commagene, there is a pool which discharges an inflammable mud, called Maltha. It adheres to every solid body which it touches, and moreover, when touched, it follows you, if you attempt to escape from it. By means of it the people defended their walls against Lucullus, and the soldiers were burned in their armour. It is even set on fire in water. We learn by experience that it can be extinguished only by earth.

CHAP. 109. —OF NAPHTHA.

Naphtha is a substance of a similar nature (it is so called about Babylon, and in the territory of the Astaceni, in Parthia), flowing like liquid bitumen. It has a great affinity to fire, which instantly darts on it wherever it is seen. It is said, that in this way it was that Medea burned Jason’s mistress; her crown having taken fire, when she approached the altar for the purpose of sacrificing.

CHAP. 110. —PLACES WHICH ARE ALWAYS BURNING.

Among the wonders of mountains there is Ætna, which always burns in the night, and for so long a period has always had materials for combustion, being in the winter buried in snow, and having the ashes which it has ejected covered with frost. Nor is it in this mountain alone that nature rages, threatening to consume the earth; in Phaselis, the mountain Chimæra burns, and indeed with a continual flame, day and night. Ctesias of Cnidos informs us, that this fire is kindled by water, while it is extinguished by earth and by hay. In the same country of Lycia, the mountains of Hephæstius, when touched with a flaming torch, burn so violently, that even the stones in the river and the sand burn, while actually in the water: this fire is also increased by rain. If a person makes furrows in the ground with a stick which has been kindled at this fire, it is said that a stream of flame will follow it. The summit of Cophantus, in Bactria, burns during the night; and this is the case in Media and at Sittacene, on the borders of Persia; likewise in Susa, at the White Tower, from fifteen apertures, the greatest of which also burns in the daytime. The plain of Babylon throws up flame from a place like a fish-pond, an acre in extent. Near Hesperium, a mountain of the Æthiopians, the fields shine in the night-time like stars; the same thing takes place in the territory of the Megalopolitani.

This fire, however, is internal, mild, and not burning the foliage of a dense wood which is over it. There is also the crater of Nymphæum, which is always burning, in the neighbourhood of a cold fountain, and which, according to Theopompus, presages direful calamities to the inhabitants of Apollonia. It is increased by rain, and it throws out bitumen, which, becoming mixed with the fountain, renders it unfit to be tasted; it is, at other times, the weakest of all the bitumens. But what are these compared to other wonders? Hiera, one of the Æolian isles, in the middle of the sea, near Italy, together with the sea itself, during the Social war, burned for several days, until expiation was made, by a deputation from the senate. There is a hill in Æthiopia called Θεῶν ὄχημα, which burns with the greatest violence, throwing out flame that consumes everything, like the sun. In so many places, and with so many fires, does nature burn the earth!

CHAP. 111. —WONDERS OF FIRE ALONE.

But since this one element is of so prolific a nature as to produce itself, and to increase from the smallest spark, what must we suppose will be the effect of all those funeral piles of the earth? What must be the nature of that thing, which, in all parts of the world, supplies this most greedy voracity without destroying itself? To these fires must be added those innumerable stars and the great sun itself. There are also the fires made by men, those which are innate in certain kinds of stones, those produced by the friction of wood, and those in the clouds, which give rise to lightning. It really exceeds all other wonders, that one single day should pass in which everything is not consumed, especially when we reflect, that concave mirrors placed opposite to the sun’s rays produce flame more readily than any other kind of fire; and that numerous small but natural fires abound everywhere. In Nymphæum there issues from a rock a fire which is kindled by rain; it also issues from the waters of the Scantia. This indeed is a feeble flame, since it passes off, remaining only a short time on any body to which it is applied: an ash tree, which overshadows this fiery spring, remains always green. In the territory of Mutina fire issues from the ground on the days that are consecrated to Vulcan. It is stated by some authors, that if a burning body falls on the fields below Aricia, the ground is set on fire; and that the stones in the territory of the Sabines and of the Sidicini, if they be oiled, burn with flame. In Egnatia, a town of Salentinum, there is a sacred stone, upon which, when wood is placed, flame immediately bursts forth. In the altar of Juno Lacinia, which is in the open air, the ashes remain unmoved, although the winds may be blowing from all quarters.

It appears also that there are sudden fires both in waters and even in the human body; that the whole of Lake Thrasymenus was on fire; that when Servius Tullius, while a child, was sleeping, flame darted out from his head; and Valerius Antias informs us, that the same flame appeared about L. Marcius, when he was pronouncing the funeral oration over the Scipios, who were killed in Spain; and exhorting the soldiers to avenge their death. I shall presently mention more facts of this nature, and in a more distinct manner; in this place these wonders are mixed up with other subjects. But my mind, having carried me beyond the mere interpretation of nature, is anxious to lead, as it were by the hand, the thoughts of my readers over the whole globe.

CHAP. 112. —THE DIMENSIONS OF THE EARTH.

Our part of the earth, of which I propose to give an account, floating as it were in the ocean which surrounds it (as I have mentioned above), stretches out to the greatest extent from east to west, viz. from India to the Pillars consecrated to Hercules at Gades, being a distance of 8568 miles, according to the statement of Artemidorus, or according to that of Isidorus, 9818 miles. Artemidorus adds to this 491 miles, from Gades, going round by the Sacred Promontory, to the promontory of Artabrum, which is the most projecting part of Spain.

This measurement may be taken in two directions. From the Ganges, at its mouth, where it discharges itself into the Eastern ocean, passing through India and Parthyene, to Myriandrus, a city of Syria, in the bay of Issus, is a distance of 5215 miles. Thence, going directly by sea, by the island of Cyprus, Patara in Lycia, Rhodes, and Astypalæa, islands in the Carpathian sea, by Tænarum in Laconia, Lilybæum in Sicily and Calaris in Sardinia, is 2103 miles. Thence to Glades is 1250 miles, making the whole distance from the Eastern ocean 8568 miles.

The other way, which is more certain, is chiefly by land. From the Ganges to the Euphrates is 5169 miles; thence to Mazaca, a town in Cappadocia, is 319 miles; thence, through Phrygia and Caria, to Ephesus is 415 miles; from Ephesus, across the Ægean sea to Delos, is 200 miles; to the Isthmus is 2121⁄2 miles; thence, first by land and afterwards by the sea of Lechæum and the gulf of Corinth, to Patræ in Peloponnesus, 90 miles; to the promontory of Leucate 871⁄2 miles; as much more to Corcyra; to the Acroceraunian mountains 1321⁄2, to Brundisium 871⁄2, and to Rome 360 miles. To the Alps, at the village of Scingomagum, is 519 miles; through Gaul to Illiberis at the Pyrenees, 927; to the ocean and the coast of Spain, 331 miles; across the passage of Gades 71⁄2 miles; which distances, according to the estimate of Artemidorus, make altogether 8945 miles.

The breadth of the earth, from south to north, is commonly supposed to be about one-half only of its length, viz. 4490 miles; hence it is evident how much the heat has stolen from it on one side and the cold on the other: for I do not suppose that the land is actually wanting, or that the earth has not the form of a globe; but that, on each side, the uninhabitable parts have not been discovered. This measure then extends from the coast of the Æthiopian ocean, the most distant part which is habitable, to Meroë, 1000 miles; thence to Alexandria 1250; to Rhodes 562; to Cnidos 871⁄2; to Cos 25; to Samos 100; to Chios 94; to Mitylene 65; to Tenedos 44; to the promontory of Sigæum 121⁄2; to the entrance of the Euxine 3121⁄2; to the promontory of Carambis 350; to the entrance of the Palus Mæotis 3121⁄2; and to the mouth of the Tanais 275 miles, which distance, if we went by sea, might be shortened 89 miles. Beyond the Tanais the most diligent authors have not been able to obtain any accurate measurement. Artemidorus supposes that everything beyond is undiscovered, since he confesses that, about the Tanais, the tribes of the Sarmatæ dwell, who extend towards the north pole. Isidorus adds 1250 miles, as the distance to Thule; but this is mere conjecture. For my part, I believe that the boundaries of Sarmatia really extend to as great a distance as that mentioned above: for if it were not very extensive, how could it contain the innumerable tribes that are always changing their residence? And indeed I consider the uninhabitable portion of the world to be still greater; for it is well known that there are innumerable islands lying off the coast of Germany, which have been only lately discovered.

The above is all that I consider worth relating about the length and the breadth of the earth. But Eratosthenes, a man who was peculiarly well skilled in all the more subtle parts of learning, and in this above everything else, and a person whom I perceive to be approved by every one, has stated the whole of this circuit to be 252,000 stadia, which, according to the Roman estimate, makes 31,500 miles. The attempt is presumptuous, but it is supported by such subtle arguments that we cannot refuse our assent. Hipparchus, whom we must admire, both for the ability with which he controverts Eratosthenes, as well as for his diligence in everything else, has added to the above number not much less than 25,000 stadia.

Dionysodorus is certainly less worthy of confidence; but I cannot omit this most remarkable instance of Grecian vanity. He was a native of Melos, and was celebrated for his knowledge of geometry; he died of old age in his native country. His female relations, who inherited his property, attended his funeral, and when they had for several successive days performed the usual rites, they are said to have found in his tomb an epistle written in his own name to those left above; it stated that he had descended from his tomb to the lowest part of the earth, and that it was a distance of 42,000 stadia. There were not wanting certain geometricians, who interpreted this epistle as if it had been sent from the middle of the globe, the point which is at the greatest distance from the surface, and which must necessarily be the centre of the sphere. Hence the estimate has been made that it is 252,000 stadia in circumference.

CHAP. 113.—THE HARMONICAL PROPORTION OF THE UNIVERSE.

That harmonical proportion, which compels nature to be always consistent with itself, obliges us to add to the above measure, 12,000 stadia; and this makes the earth one ninety-sixth part of the whole universe.

Summary.—The facts, statements, and observations contained in this Book amount in number to 417.

Roman authors quoted.—M. Varro, Sulpicius Gallus, Titus Cæsar the Emperor, Q. Tubero, Tullius Tiro, L. Piso, T. Livius, Cornelius Nepos, Sebosus, Cælius Antipater,

Fabianus, Antias, Mucianus, Cæcina, who wrote on the Etruscan discipline, Tarquitius, who did the same, Julius Aquila, who also did the same, and Sergius.

Foreign authors quoted.—Plato, Hipparchus, Timæus, Sosigenes, Petosiris, Necepsos,

the Pythagorean Philosophers, Posidonius, Anaximander, Epigenes the philosopher who wrote on Gnomonics, Euclid, Cœranus the philosopher, Eudoxus, Democritus, Critodemus, Thrasyllus, Serapion, Dicæarchus, Archimedes,

Onesicritus, Eratosthenes, Pytheas, Herodotus, Aristotle, Ctesias, Artemidorus of Ephesus, Isidorus of Charax, and Theopompus.