Editors Note

This is Book II – Part IV of the thirty seven books in Plinys’ Natural History. In order to make the collection more accessible and easier to navigate, most of the books have been divided into several parts. This book has been divided into six parts:

Part I – On God, the World, the Planets, the Sun and the Moon

Part II – On Stars and their characteristics, Meteors, Comets and Solar or Lunar Eclipses

Part III – On Seasons, Weather, Winds, Thunder and Lightning

Part IV – On Weather, the Earth, Climate and Daylight

Part V – On Earthquakes, Islands evolution, and Effects of the Sea on Land

Part VI – On the Sea, Fire, Dimensions of the Earth and the Universe

Translated by John Bostock MD, F.R.S (1773-1846) and Henry T. Riley Esq., B.A. (1816-1878), first published 1855. No changes have been made to the text, however all footnotes have been removed.

CHAP. 60. —THE RAINBOW.

What we name Rainbows frequently occur, and are not considered either wonderful or ominous; for they do not predict, with certainty, either rain or fair weather. It is obvious, that the rays of the sun, being projected upon a hollow cloud, the light is thrown back to the sun and is refracted, and that the variety of colours is produced by a mixture of clouds, air, and fire. The rainbow is certainly never produced except in the part opposite to the sun, nor even in any other form except that of a semicircle. Nor are they ever formed at night, although Aristotle asserts that they are sometimes seen at that time; he acknowledges, however, that it can only be on the 14th day of the moon. They are seen in the winter the most frequently, when the days are shortening, after the autumnal equinox. They are not seen when the days increase again, after the vernal equinox, nor on the longest days, about the summer solstice, but frequently at the winter solstice, when the days are the shortest. When the sun is low they are high, and when the sun is high they are low; they are smaller when in the east or west, but are spread out wider; in the south they are small, but of a greater span. In the summer they are not seen at noon, but after the autumnal equinox at any hour: there are never more than two seen at once.

CHAP. 61.—THE NATURE OF HAIL, SNOW, HOAR, MIST, DEW; THE FORMS OF CLOUDS.

I do not find that there is any doubt entertained respecting the following points. (60.) Hail is produced by frozen rain, and snow by the same fluid less firmly concreted, and hoar by frozen dew. During the winter snow falls, but not hail; hail itself falls more frequently during the day than the night, and is more quickly melted than snow. There are no mists either in the summer or during the greatest cold of winter. There is neither dew nor hoar formed during great heat or winds, nor unless the night be serene. Fluids are diminished in bulk by being frozen, and, when the ice is melted, we do not obtain the same quantity of fluid as at first.

The clouds are varied in their colour and figure according as the fire which they contain is in excess or is absorbed by them.

CHAP. 62. —THE PECULIARITIES OF THE WEATHER IN DIFFERENT PLACES.

There are, moreover, certain peculiarities in certain places. In Africa dew falls during the night in summer. In Italy, at Locri, and at the Lake Velinum, there is never a day in which a rainbow is not seen. At Rhodes and at Syracuse the sky is never so covered with clouds, but that the sun is visible at one time or another; these things, however, will be better detailed in their proper place. So far respecting the air.

CHAP. 63. —NATURE OF THE EARTH.

Next comes the earth, on which alone of all parts of nature we have bestowed the name that implies maternal veneration. It is appropriated to man as the heavens are to God. She receives us at our birth, nourishes us when born, and ever afterwards supports us; lastly, embracing us in her bosom when we are rejected by the rest of nature, she then covers us with especial tenderness; rendered sacred to us, inasmuch as she renders us sacred, bearing our monuments and titles, continuing our names, and extending our memory, in opposition to the shortness of life. In our anger we imprecate her on those who are now no more, as if we were ignorant that she is the only being who can never be angry with man. The water passes into showers, is concreted into hail, swells into rivers, is precipitated in torrents; the air is condensed into clouds, rages in squalls; but the earth, kind, mild, and indulgent as she is, and always ministering to the wants of mortals, how many things do we compel her to produce spontaneously! What odours and flowers, nutritive juices, forms and colours! With what good faith does she render back all that has been entrusted to her! It is the vital spirit which must bear the blame of producing noxious animals; for the earth is constrained to receive the seeds of them, and to support them when they are produced. The fault lies in the evil nature which generates them. The earth will no longer harbour a serpent after it has attacked any one, and thus she even demands punishment in the name of those who are indifferent about it themselves. She pours forth a profusion of medicinal plants, and is always producing something for the use of man. We may even suppose, that it is out of compassion to us that she has ordained certain substances to be poisonous, in order that when we are weary of life, hunger, a mode of death the most foreign to the kind disposition of the earth, might not consume us by a slow decay, that precipices might not lacerate our mangled bodies, that the unseemly punishment of the halter may not torture us, by stopping the breath of one who seeks his own destruction, or that we may not seek our death in the ocean, and become food for our graves, or that our bodies may not be gashed by steel. On this account it is that nature has produced a substance which is very easily taken, and by which life is extinguished, the body remaining undefiled and retaining all its blood, and only causing a degree of thirst. And when it is destroyed by this means, neither bird nor beast will touch the body, but he who has perished by his own hands is reserved for the earth.

But it must be acknowledged, that everything which the earth has produced, as a remedy for our evils, we have converted into the poison of our lives. For do we not use iron, which we cannot do without, for this purpose? But although this cause of mischief has been produced, we ought not to complain; we ought not to be ungrateful to this one part of nature. How many luxuries and how many insults does she not bear for us! She is cast into the sea, and, in order that we may introduce seas into her bosom, she is washed away by the waves. She is continually tortured for her iron, her timber, stone, fire, corn, and is even much more subservient to our luxuries than to our mere support. What indeed she endures on her surface might be tolerated, but we penetrate also into her bowels, digging out the veins of gold and silver, and the ores of copper and lead; we also search for gems and certain small pebbles, driving our trenches to a great depth. We tear out her entrails in order to extract the gems with which we may load our fingers. How many hands are worn down that one little joint may be ornamented! If the infernal regions really existed, certainly these burrows of avarice and luxury would have penetrated into them. And truly we wonder that this same earth should have produced anything noxious! But, I suppose, the savage beasts protect her and keep off our sacrilegious hands. For do we not dig among serpents and handle poisonous plants along with those veins of gold? But the Goddess shows herself more propitious to us, inasmuch as all this wealth ends in crimes, slaughter, and war, and that, while we drench her with our blood, we cover her with unburied bones; and being covered with these and her anger being thus appeased, she conceals the crimes of mortals. I consider the ignorance of her nature as one of the evil effects of an ungrateful mind.

CHAP. 64. —OF THE FORM OF THE EARTH.

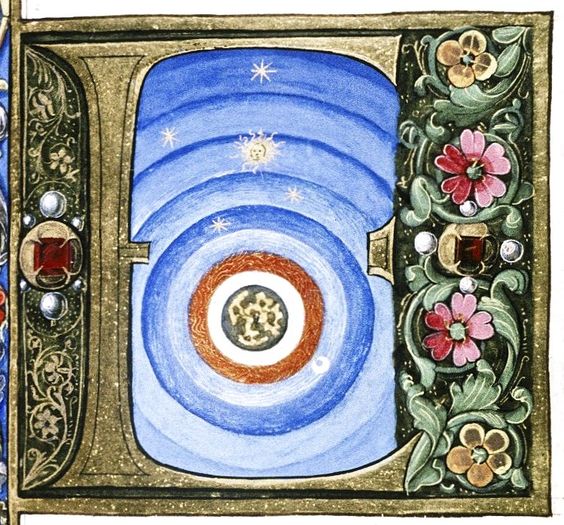

Every one agrees that it has the most perfect figure. We always speak of the ball of the earth, and we admit it to be a globe bounded by the poles. It has not indeed the form of an absolute sphere, from the number of lofty mountains and flat plains; but if the termination of the lines be bounded by a curve, this would compose a perfect sphere. And this we learn from arguments drawn from the nature of things, although not from the same considerations which we made use of with respect to the heavens. For in these the hollow convexity everywhere bends on itself, and leans upon the earth as its centre. Whereas the earth rises up solid and dense, like something that swells up and is protruded outwards. The heavens bend towards the centre, while the earth goes from the centre, the continual rolling of the heavens about it forcing its immense globe into the form of a sphere.

CHAP. 65. —WHETHER THERE BE ANTIPODES?

On this point there is a great contest between the learned and the vulgar. We maintain, that there are men dispersed over every part of the earth, that they stand with their feet turned towards each other, that the vault of the heavens appears alike to all of them, and that they, all of them, appear to tread equally on the middle of the earth. If any one should ask, why those situated opposite to us do not fall, we directly ask in return, whether those on the opposite side do not wonder that we do not fall. But I may make a remark, that will appear plausible even to the most unlearned, that if the earth were of the figure of an unequal globe, like the seed of a pine, still it may be inhabited in every part.

But of how little moment is this, when we have another miracle rising up to our notice! The earth itself is pendent and does not fall with us; it is doubtful whether this be from the force of the spirit which is contained in the universe, or whether it would fall, did not nature resist, by allowing of no place where it might fall. For as the seat of fire is nowhere but in fire, nor of water except in water, nor of air except in air, so there is no situation for the earth except in itself, everything else repelling it. It is indeed wonderful that it should form a globe, when there is so much flat surface of the sea and of the plains. And this was the opinion of Dicæarchus, a peculiarly learned man, who measured the heights of mountains, under the direction of the kings, and estimated Pelion, which was the highest, at 1250 paces perpendicular, and considered this as not affecting the round figure of the globe. But this appears to me to be doubtful, as I well know that the summits of some of the Alps rise up by a long space of not less than 50,000 paces. But what the vulgar most strenuously contend against is, to be compelled to believe that the water is forced into a rounded figure; yet there is nothing more obvious to the sight among the phænomena of nature. For we see everywhere, that drops, when they hang down, assume the form of small globes, and when they are covered with dust, or have the down of leaves spread over them, they are observed to be completely round; and when a cup is filled, the liquid swells up in the middle. But on account of the subtile nature of the fluid and its inherent softness, the fact is more easily ascertained by our reason than by our sight. And it is even more wonderful, that if a very little fluid only be added to a cup when it is full, the superfluous quantity runs over, whereas the contrary happens if we add a solid body, even as much as would weigh 20 denarii. The reason of this is, that what is dropt in raises up the fluid at the top, while what is poured on it slides off from the projecting surface. It is from the same cause that the land is not visible from the body of a ship when it may be seen from the mast; and that when a vessel is receding, if any bright object be fixed to the mast, it seems gradually to descend and finally to become invisible. And the ocean, which we admit to be without limits, if it had any other figure, could it cohere and exist without falling, there being no external margin to contain it? And the same wonder still recurs, how is it that the extreme parts of the sea, although it be in the form of a globe, do not fall down? In opposition to which doctrine, the Greeks, to their great joy and glory, were the first to teach us, by their subtile geometry, that this could not happen, even if the seas were flat, and of the figure which they appear to be. For since water always runs from a higher to a lower level, and this is admitted to be essential to it, no one ever doubted that the water would accumulate on any shore, as much as its slope would allow it. It is also certain, that the lower anything is, so much the nearer is it to the centre, and that all the lines which are drawn from this point to the water which is the nearest to it, are shorter than those which reach from the beginning of the sea to its extreme parts. Hence it follows, that all the water, from every part, tends towards the centre, and, because it has this tendency, does not fall.

CHAP. 66.—HOW THE WATER IS CONNECTED WITH THE EARTH. OF THE NAVIGATION OF THE SEA AND THE RIVERS.

We must believe, that the great artist, Nature, has so arranged it, that as the arid and dry earth cannot subsist by itself and without moisture, nor, on the other hand, can the water subsist unless it be supported by the earth, they are connected by a mutual union. The earth opens her harbours, while the water pervades the whole earth, within, without, and above; its veins running in all directions, like connecting links, and bursting out on even the highest ridges; where, forced up by the air, and pressed out by the weight of the earth, it shoots forth as from a pipe, and is so far from being in danger of falling, that it bounds up to the highest and most lofty places. Hence the reason is obvious, why the seas are not increased by the daily accession of so many rivers.

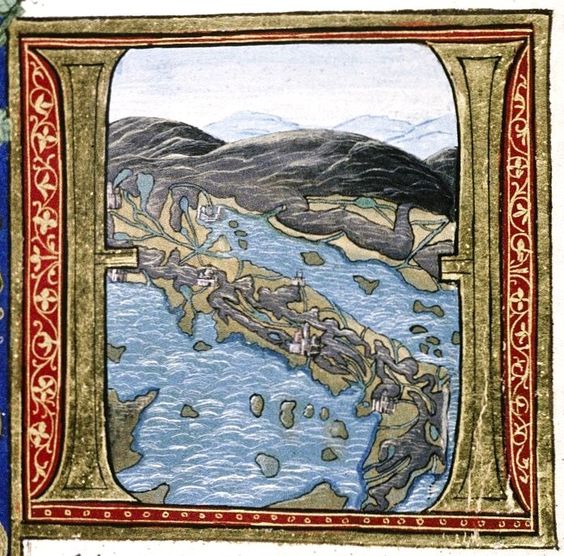

The earth has, therefore, the whole of its globe girt, on every side, by the sea flowing round it. And this is not a point to be investigated by arguments, but what has been ascertained by experience.

CHAP. 67. —WHETHER THE OCEAN SURROUNDS THE EARTH.

The whole of the western ocean is now navigated, from Gades and the Pillars of Hercules, round Spain and Gaul. The greater part of the northern ocean has also been navigated, under the auspices of the Emperor Augustus, his fleet having been carried round Germany to the promontory of the Cimbri; from which spot they descried an immense sea, or became acquainted with it by report, which extends to the country of the Scythians, and the districts that are chilled by excessive moisture. On this account it is not at all probable, that the ocean should be deficient in a region where moisture so much abounds. In like manner, towards the east, from the Indian sea, all that part which lies in the same latitude, and which bends round towards the Caspian, has been explored by the Macedonian arms, in the reigns of Seleucus and Antiochus, who wished it to be named after themselves, the Seleucian or Antiochian Sea. About the Caspian, too, many parts of the shores of the ocean have been explored, so that nearly the whole of the north has been sailed over in one direction or another. Nor can our argument be much affected by the point that has been so much discussed, respecting the Palus Mæotis, whether it be a bay of the same ocean, as is, I understand, the opinion of some persons, or whether it be the overflowing of a narrow channel connected with a different ocean. On the other side of Gades, proceeding from the same western point, a great part of the southern ocean, along Mauritania, has now been navigated. Indeed the greater part of this region, as well as of the east, as far as the Arabian Gulf, was surveyed in consequence of Alexander’s victories. When Caius Cæsar, the son of Augustus, had the conduct of affairs in that country, it is said that they found the remains of Spanish vessels which had been wrecked there. While the power of Carthage was at its height, Hanno published an account of a voyage which he made from Gades to the extremity of Arabia; Himilco was also sent, about the same time, to explore the remote parts of Europe. Besides, we learn from Corn. Nepos, that one Eudoxus, a contemporary of his, when he was flying from king Lathyrus, set out from the Arabian Gulf, and was carried as far as Gades. And long before him, Cælius Antipater informs us, that he had seen a person who had sailed from Spain to Æthiopia for the purposes of trade. The same Cornelius Nepos, when speaking of the northern circumnavigation, tells us that Q. Metellus Celer, the colleague of L. Afranius in the consulship, but then a proconsul in Gaul, had a present made to him by the king of the Suevi, of certain Indians, who sailing from India for the purpose of commerce, had been driven by tempests into Germany. Thus it appears, that the seas which flow completely round the globe, and divide it, as it were, into two parts, exclude us from one part of it, as there is no way open to it on either side. And as the contemplation of these things is adapted to detect the vanity of mortals, it seems incumbent on me to display, and lay open to our eyes, the whole of it, whatever it be, in which there is nothing which can satisfy the desires of certain individuals.

CHAP. 68. —WHAT PART OF THE EARTH IS INHABITED.

In the first place, then, it appears that this should be estimated at half the globe, as if no portion of this half was encroached upon by the ocean. But surrounding as it does the whole of the land, pouring out and receiving all the other waters, furnishing whatever goes to the clouds, and feeding the stars themselves, so numerous and of such great size as they are, what a great space must we not suppose it to occupy! This vast mass must fill up and occupy an infinite extent. To this we must add that portion of the remainder which the heavens take from us. For the globe is divided into five parts, termed zones, and all that portion is subject to severe cold and perpetual frost which is under the two extremities, about each of the poles, the nearer of which is called the north, and the opposite the south, pole. In all these regions there is perpetual darkness, and, in consequence of the aspect of the milder stars being turned from them, the light is malignant, and only like the whiteness which is produced by hoar frost. The middle of the earth, over which is the orbit of the sun, is parched and burned by the flame, and is consumed by being so near the heat. There are only two of the zones which are temperate, those which lie between the torrid and the frigid zones, and these are separated from each other, in consequence of the scorching heat of the heavenly bodies.

It appears, therefore, that the heavens take from us three parts of the earth; how much the ocean steals is uncertain.

And with respect to the part which is left us, I do not know whether that is not even in greater danger. This same ocean, insinuating itself, as I have described it, into a number of bays, approaches with its roaring so near to the inland seas, that the Arabian Gulf is no more than 115 miles from the Egyptian Sea, and the Caspian only 375 miles from the Euxine. It also insinuates itself into the numerous seas by which it separates Africa, Europe, and Asia; hence how much space must it occupy? We must also take into account the extent of all the rivers and the marshes, and we must add the lakes and the pools. There are also the mountains, raised up to the heavens, with their precipitous fronts; we must also subtract the forests and the craggy valleys, the wildernesses, and the places, which, from various causes, are desert. The vast quantity which remains of the earth, or rather, as many persons have considered it, this speck of a world (for the earth is no more in regard to the universe), this is the object, the seat of our glory—here we bear our honours, here we exercise our power, here we covet wealth, here we mortals create our disturbances, here we continually carry on our wars, aye, civil wars, even, and unpeople the earth by mutual slaughter. And not to dwell on public feuds, entered into by nations against each other, here it is that we drive away our neighbours, and enclose the land thus seized upon within our own fence; and yet the man who has most extended his boundary, and has expelled the inhabitants for ever so great a distance, after all, what mighty portion of the earth is he master of? And even when his avarice has been the most completely satisfied, what part of it can he take with him into the grave?

CHAP. 69. —THAT THE EARTH IS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE WORLD.

It is evident from undoubted arguments, that the earth is in the middle of the universe, but it is the most clearly proved by the equality of the days and the nights at the equinox. It is demonstrated by the quadrant, which affords the most decisive confirmation of the fact, that unless the earth was in the middle, the days and nights could not be equal; for, at the time of the equinox, the rising and setting of the sun are seen on the same line, and the rising of the sun, at the summer solstice, is on the same line with its setting at the winter solstice; but this could not happen if the earth was not situated in the centre.

CHAP. 70. —OF THE OBLIQUITY OF THE ZONES.

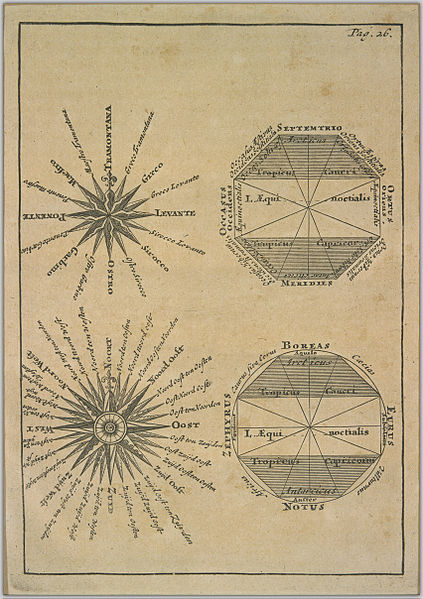

The three circles, which are connected with the above-mentioned zones, distinguish the inequalities of the seasons; these are, the solstitial circle, which proceeds from the part of the Zodiac the highest to us and approaching the nearest to the district of the north; on the other side, the brumal, which is towards the south pole; and the equinoctial, which traverses the middle of the Zodiac.

CHAP. 71.—OF THE INEQUALITY OF CLIMATES.

The cause of the other things which are worthy of our admiration depends on the figure of the earth itself, which, together with all its waters, is proved, by the same arguments, to be a globe. This certainly is the cause why the stars of the northern portion of the heavens never set to us, and why, on the other hand, those in the south never rise, and again, why the latter can never be seen by the former, the globe of the earth rising up and concealing them. The Northern Wain is never seen in Troglodytice, nor in Egypt, which borders on it; nor can we, in Italy, see the star Canopus, or Berenice’s Hair; nor what, under the Emperor Augustus, was named Cæsar’s Throne, although they are, there, very brilliant stars. The curved form of the earth is so obvious, rising up like a ridge, that Canopus appears to a spectator at Alexandria to rise above the horizon almost the quarter of a sign; the same star at Rhodes appears, as it were, to graze along the earth, while in Pontus it is not seen at all; where the Northern Wain appears considerably elevated. This same constellation cannot be seen at Rhodes, and still less at Alexandria. In Arabia, in the month of November, it is concealed during the first watch of the night, but may be seen during the second; in Meroë it is seen, for a short time, in the evening, at the solstice, and it is visible at day-break, for a few days before the rising of Arcturus. These facts have been principally ascertained by the expeditions of navigators; the sea appearing more elevated or depressed in certain parts; the stars suddenly coming into view, and, as it were, emerging from the water, after having been concealed by the bulging out of the globe. But the heavens do not, as some suppose, rise higher at one pole, otherwise its stars would be seen from all parts of the world; they indeed are supposed to be higher by those who are nearest to them, but the stars are sunk below the horizon to those who are more remote. As this pole appears to be elevated to those who are beneath it; so, when we have passed along the convexity of the earth, those stars rise up, which appear elevated to the inhabitants of those other districts; all this, however, could not happen unless the earth had the shape of a globe.

CHAP. 72.—IN WHAT PLACES ECLIPSES ARE INVISIBLE, AND WHY THIS IS THE CASE.

Hence it is that the inhabitants of the east do not see those eclipses of the sun or of the moon which occur in the evening, nor the inhabitants of the west those in the morning, while such as take place at noon are more frequently visible. We are told, that at the time of the famous victory of Alexander the Great, at Arbela, the moon was eclipsed at the second hour of the night, while, in Sicily, the moon was rising at the same hour. The eclipse of the sun which occurred the day before the calends of May, in the consulship of Vipstanus and Fonteius, not many years ago, was seen in Campania between the seventh and eighth hour of the day; the general Corbulo informs us, that it was seen in Armenia, between the eleventh and twelfth hour; thus the curve of the globe both reveals and conceals different objects from the inhabitants of its different parts. If the earth had been flat, everything would have been seen at the same time, from every part of it, and the nights would not have been unequal; while the equal intervals of twelve hours, which are now observed only in the middle of the earth, would in that case have been the same everywhere.

CHAP. 73. —WHAT REGULATES THE DAYLIGHT ON THE EARTH.

Hence it is that there is not any one night and day the same, in all parts of the earth, at the same time; the intervention of the globe producing night, and its turning round producing day. This is known by various observations. In Africa and in Spain it is made evident by the Towers of Hannibal, and in Asia by the beacons, which, in consequence of their dread of pirates, the people erected for their protection; for it has been frequently observed, that the signals, which were lighted at the sixth hour of the day, were seen at the third hour of the night by those who were the most remote. Philonides, a courier of the above-mentioned Alexander, went from Sicyon to Elis, a distance of 1200 stadia, in nine hours, while he seldom returned until the third hour of the night, although the road was down-hill. The reason is, that, in going, he followed the course of the sun, while on his return, in the opposite direction, he met the sun and left it behind him. For the same reason it is, that those who sail to the west, even on the shortest day, compensate for the difficulty of sailing in the night and go farther, because they sail in the same direction with the sun.

CHAP. 74. —REMARKS ON DIALS, AS CONNECTED WITH THIS SUBJECT.

The same dial-plates cannot be used in all places, the shadow of the sun being sensibly different at distances of 300, or at most of 500 stadia. Hence the shadow of the dial-pin, which is termed the gnomon, at noon and at the summer solstice, in Egypt, is a little more than half the length of the gnomon itself. At the city of Rome it is only 1⁄9 less than the gnomon, at Ancona not more than 1⁄35 less, while in the part of Italy which is called Venetia, at the same hour, the shadow is equal to the length of the gnomon.

CHAP. 75. —WHEN AND WHERE THERE ARE NO SHADOWS.

It is likewise said, that in the town of Syene, which is 5000 stadia south of Alexandria, there is no shadow at noon, on the day of the solstice; and that a well, which was sunk for the purpose of the experiment, is illuminated by the sun in every part. Hence it appears that the sun, in this place, is vertical, and Onesicritus informs us that this is the case, about the same time, in India, at the river Hypasis. It is well known, that at Berenice, a city of the Troglodytæ, and 4820 stadia beyond that city, in the same country, at the town of Ptolemais, which was built on the Red Sea, when the elephant was first hunted, this same thing takes place for forty-five days before the solstice and for an equal length of time after it, and that during these ninety days the shadows are turned towards the south. Again, at Meroë, an island in the Nile and the metropolis of the Æthiopians, which is 5000 stadia from Syene, there are no shadows at two periods of the year, viz. when the sun is in the 18th degree of Taurus and in the 14th of Leo. The Oretes, a people of India, have a mountain named Maleus, near which the shadows in summer fall towards the south and in winter towards the north. The seven stars of the Great Bear are visible there for fifteen nights only. In India also, in the celebrated sea-port Patale, the sun rises to the right hand and the shadows fall towards the south. While Alexander was staying there it was observed, that the seven northern stars were seen only during the early part of the night. Onesicritus, one of his generals, informs us in his work, that in those places in India where there are no shadows, the seven stars are not visible; these places, he says, are called “Ascia,” and the people there do not reckon the time by hours.

CHAP. 76. —-WHERE THIS TAKES PLACE TWICE IN THE YEAR AND WHERE THE SHADOWS FALL IN OPPOSITE DIRECTIONS.

Eratosthenes informs us, that in the whole of Troglodytice, for twice forty-five days in the year, the shadows fall in the contrary direction.

CHAP. 77. —WHERE THE DAYS ARE THE LONGEST AND WHERE THE SHORTEST.

Hence it follows, that in consequence of the daylight increasing in various degrees, in Meroë the longest day consists of twelve æquinoctial hours and eight parts of an hour, at Alexandria of fourteen hours, in Italy of fifteen, in Britain of seventeen; where the degree of light, which exists in the night, very clearly proves, what the reason of the thing also obliges us to believe, that, during the solstitial period, as the sun approaches to the pole of the world, and his orbit is contracted, the parts of the earth that lie below him have a day of six months long, and a night of equal length when he is removed to the south pole. Pytheas, of Marseilles, informs us, that this is the case in the island of Thule, which is six days’ sail from the north of Britain. Some persons also affirm that this is the case in Mona, which is about 200 miles from Camelodunum, a town of Britain.

CHAP. 78. —OF THE FIRST DIAL.

Anaximenes the Milesian, the disciple of Anaximander, of whom I have spoken above, discovered the theory of shadows and what is called the art of dialling, and he was the first who exhibited at Lacedæmon the dial which they call sciothericon.

CHAP. 79. —OF THE MODE IN WHICH THE DAYS ARE COMPUTED.

The days have been computed by different people in different ways. The Babylonians reckoned from one sunrise to the next; the Athenians from one sunset to the next; the Umbrians from noon to noon; the multitude, universally, from light to darkness; the Roman priests and those who presided over the civil day, also the Egyptians and Hipparchus, from midnight to midnight. It appears that the interval from one sunrise to the next is less near the solstices than near the equinoxes, because the position of the zodiac is more oblique about its middle part, and more straight near the solstice.

CHAP. 80. —OF THE DIFFERENCE OF NATIONS AS DEPENDING ON THE NATURE OF THE WORLD.

To these circumstances we must add those that are connected with certain celestial causes. There can be no doubt, that the Æthiopians are scorched by their vicinity to the sun’s heat, and they are born, like persons who have been burned, with the beard and hair frizzled; while, in the opposite and frozen parts of the earth, there are nations with white skins and long light hair. The latter are savage from the inclemency of the climate, while the former are dull from its variableness. We learn, from the form of the legs, that in the one, the fluids, like vapour, are forced into the upper parts of the body, while in the other, being a gross humour, it is drawn downwards into the lower parts. In the cold regions savage beasts are produced, and in the others, various forms of animals, and many kinds of birds. In both situations the body grows tall, in the one case by the force of fire, and in the other by the nutritive moisture.

In the middle of the earth there is a salutary mixture of the two, a tract fruitful in all things, the habits of the body holding a mean between the two, with a proper tempering of colours; the manners of the people are gentle, the intellect clear, the genius fertile and capable of comprehending every part of nature. They have formed empires, which has never been done by the remote nations; yet these latter have never been subjected by the former, being severed from them and remaining solitary, from the effect produced on them by their savage nature.