Editors Note

This is Book II – Part V of the thirty seven books in Plinys’ Natural History. In order to make the collection more accessible and easier to navigate, most of the books have been divided into several parts. This book has been divided into six parts:

Part I – On God, the World, the Planets, the Sun and the Moon

Part II – On Stars and their characteristics, Meteors, Comets and Solar or Lunar Eclipses

Part III – On Seasons, Weather, Winds, Thunder and Lightning

Part IV – On Weather, the Earth, Climate and Daylight

Part V – On Earthquakes, Islands evolution, and Effects of the Sea on Land

Part VI – On the Sea, Fire, Dimensions of the Earth and the Universe

Translated by John Bostock MD, F.R.S (1773-1846) and Henry T. Riley Esq., B.A. (1816-1878), first published 1855. No changes have been made to the text, however all footnotes have been removed.

CHAP. 81. —OF EARTHQUAKES.

According to the doctrine of the Babylonians, earthquakes and clefts of the earth, and occurrences of this kind, are supposed to be produced by the influence of the stars, especially of the three to which they ascribe thunder; and to be caused by the stars moving with the sun, or being in conjunction with it, and, more particularly, when they are in the quartile aspect. If we are to credit the report, a most admirable and immortal spirit, as it were of a divine nature, should be ascribed to Anaximander the Milesian, who, they say, warned the Lacedæmonians to beware of their city and their houses. For he predicted that an earthquake was at hand, when both the whole of their city was destroyed and a large portion of Mount Taygetus, which projected in the form of a ship, was broken off, and added farther ruin to the previous destruction. Another prediction is ascribed to Pherecydes, the master of Pythagoras, and this was divine; by a draught of water from a well, he foresaw and predicted that there would be an earthquake in that place. And if these things be true, how nearly do these individuals approach to the Deity, even during their lifetime! But I leave every one to judge of these matters as he pleases. I certainly conceive the winds to be the cause of earthquakes; for the earth never trembles except when the sea is quite calm, and when the heavens are so tranquil that the birds cannot maintain their flight, all the air which should support them being withdrawn; nor does it ever happen until after great winds, the gust being pent up, as it were, in the fissures and concealed hollows. For the trembling of the earth resembles thunder in the clouds; nor does the yawning of the earth differ from the bursting of the lightning; the enclosed air struggling and striving to escape.

CHAP. 82. —OF CLEFTS OF THE EARTH.

The earth is shaken in various ways, and wonderful effects are produced; in one place the walls of cities being thrown down, and in others swallowed up by a deep cleft; sometimes great masses of earth are heaped up, and rivers forced out, sometimes even flame and hot springs, and at others the course of rivers is turned. A terrible noise precedes and accompanies the shock; sometimes a murmuring, like the lowing of cattle, or like human voices, or the clashing of arms. This depends on the substance which receives the sound, and the shape of the caverns or crevices through which it issues; it being more shrill from a narrow opening, more hoarse from one that is curved, producing a loud reverberation from hard bodies, a sound like a boiling fluid from moist substances, fluctuating in stagnant water, and roaring when forced against solid bodies. There is, therefore, often the sound without any motion. Nor is it a simple motion, but one that is tremulous and vibratory. The cleft sometimes remains, displaying what it has swallowed up; sometimes concealing it, the mouth being closed and the soil being brought over it, so that no vestige is left; the city being, as it were, devoured, and the tract of country engulfed. Maritime districts are more especially subject to shocks. Nor are mountainous tracts exempt from them; I have found, by my inquiries, that the Alps and the Apennines are frequently shaken. The shocks happen more frequently in the autumn and in the spring, as is the case also with thunder. There are seldom shocks in Gaul and in Egypt; in the latter it depends on the prevalence of summer, in the former, of winter. They also happen more frequently in the night than in the day. The greatest shocks are in the morning and the evening; but they often take place at day-break, and sometimes at noon. They also take place during eclipses of the sun and of the moon, because at that time storms are lulled. They are most frequent when great heat succeeds to showers, or showers succeed to great heat.

CHAP. 83. —SIGNS OF AN APPROACHING EARTHQUAKE.

There is no doubt that earthquakes are felt by persons on shipboard, as they are struck by a sudden motion of the waves, without these being raised by any gust of wind. And things that are in the vessels shake as they do in houses, and give notice by their creaking; also the birds, when they settle upon the vessels, are not without their alarms. There is also a sign in the heavens; for, when a shock is near at hand, either in the daytime or a little after sunset, a cloud is stretched out in the clear sky, like a long thin line. The water in wells is also more turbid than usual, and it emits a disagreeable odour.

CHAP. 84. —PRESERVATIVES AGAINST FUTURE EARTHQUAKES.

These same places, however, afford protection, and this is also the case where there is a number of caverns, for they give vent to the confined vapour, a circumstance which has been remarked in certain towns, which have been less shaken where they have been excavated by many sewers. And, in the same town, those parts that are excavated are safer than the other parts, as is understood to be the case at Naples in Italy, the part of it which is solid being more liable to injury. Arched buildings are also the most safe, also the angles of walls, the shocks counteracting each other; walls made of brick also suffer less from the shocks. There is also a great difference in the nature of the motions, where various motions are experienced. It is the safest when it vibrates and causes a creaking in the building, and where it swells and rises upwards, and settles with an alternate motion. It is also harmless when the buildings coming together butt against each other in opposite directions, for the motions counteract each other. A movement like the rolling of waves is dangerous, or when the motion is impelled in one direction. The tremors cease when the vapour bursts out; but if they do not soon cease, they continue for forty days; generally, indeed, for a longer time: some have lasted even for one or two years.

CHAP. 85. —PRODIGIES OF THE EARTH WHICH HAVE OCCURRED ONCE ONLY.

A great prodigy of the earth, which never happened more than once, I have found mentioned in the books of the Etruscan ceremonies, as having taken place in the district of Mutina, during the consulship of Lucius Martius and Sextus Julius. Two mountains rushed together, falling upon each other with a very loud crash, and then receding; while in the daytime flame and smoke issued from them; a great crowd of Roman knights, and families of people, and travellers on the Æmilian way, being spectators of it. All the farm-houses were thrown down by the shock, and a great number of animals that were in them were killed; it was in the year before the Social war; and I am in doubt whether this event or the civil commotions were more fatal to the territory of Italy. The prodigy which happened in our own age was no less wonderful; in the last year of the emperor Nero, as I have related in my history of his times, when certain fields and olive grounds in the district of Marrucinum, belonging to Vectius Marcellus, a Roman knight, the steward of Nero, changed places with each other, although the public highway was interposed.

CHAP. 86. —WONDERFUL CIRCUMSTANCES ATTENDING EARTHQUAKES.

Inundations of the sea take place at the same time with earthquakes; the water being impregnated with the same spirit, and received into the bosom of the earth which subsides. The greatest earthquake which has occurred in our memory was in the reign of Tiberius, by which twelve cities of Asia were laid prostrate in one night. They occurred the most frequently during the Punic war, when we had accounts brought to Rome of fifty-seven earthquakes in the space of a single year. It was during this year that the Carthaginians and the Romans, who were fighting at the lake Thrasimenus, were neither of them sensible of a very great shock during the battle. Nor is it an evil merely consisting in the danger which is produced by the motion; it is an equal or a greater evil when it is considered as a prodigy. The city of Rome never experienced a shock, which was not the forerunner of some great calamity.

CHAP. 87. —IN WHAT PLACES THE SEA HAS RECEDED.

The same cause produces an increase of the land; the vapour, when it cannot burst out forcibly lifting up the surface. For the land is not merely produced by what is brought down the rivers, as the islands called Echinades are formed by the river Achelous, and the greater part of Egypt by the Nile, where, according to Homer, it was a day and a night’s journey from the main land to the island of Pharos; but, in some cases, by the receding of the sea, as, according to the same author, was the case with the Circæan isles. The same thing also happened in the harbour of Ambracia, for a space of 10,000 paces, and was also said to have taken place for 5000 at the Piræus of Athens, and likewise at Ephesus, where formerly the sea washed the walls of the temple of Diana. Indeed, if we may believe Herodotus, the sea came beyond Memphis, as far as the mountains of Æthiopia, and also from the plains of Arabia. The sea also surrounded Ilium and the whole of Teuthrania, and covered the plain through which the Mæander flows.

CHAP. 88. —THE MODE IN WHICH ISLANDS RISE UP.

Land is sometimes formed in a different manner, rising suddenly out of the sea, as if nature was compensating the earth for its losses, restoring in one place what she had swallowed up in another.

CHAP. 89. —WHAT ISLANDS HAVE BEEN FORMED, AND AT WHAT PERIODS.

Delos and Rhodes, islands which have now been long famous, are recorded to have risen up in this way. More lately there have been some smaller islands formed; Anapha, which is beyond Melos; Nea, between Lemnos and the Hellespont; Halone, between Lebedos and Teos; Thera and Therasia, among the Cyclades, in the fourth year of the 135th Olympiad. And among the same islands, 130 years afterwards, Hiera, also called Automate, made its appearance; also Thia, at the distance of two stadia from the former, 110 years afterwards, in our own times, when M. Junius Silanus and L. Balbus were consuls, on the 8th of the ides of July.

Opposite to us, and near to Italy, among the Æolian isles, an island emerged from the sea; and likewise one near Crete, 2500 paces in extent, and with warm springs in it; another made its appearance in the third year of the 163rd Olympiad, in the Tuscan gulf, burning with a violent explosion. There is a tradition too that a great number of fishes were floating about the spot, and that those who employed them for food immediately expired. It is said that the Pithecusan isles rose up, in the same way, in the bay of Campania, and that, shortly afterwards, the mountain Epopos, from which flame had suddenly burst forth, was reduced to the level of the neighbouring plain. In the same island, it is said, that a town was sunk in the sea; that in consequence of another shock, a lake burst out, and that, by a third, Prochytas was formed into an island, the neighbouring mountains being rolled away from it.

CHAP 90.—LANDS WHICH HAVE BEEN SEPARATED BY THE SEA.

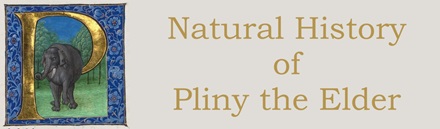

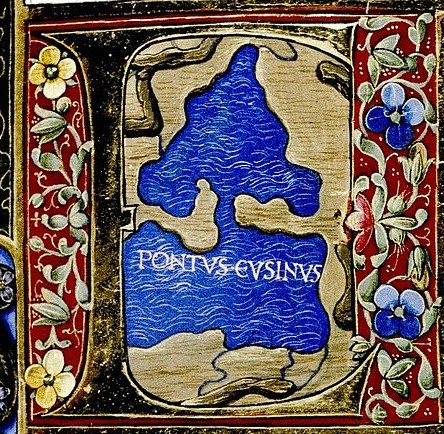

In the ordinary course of things islands are also formed by this means. The sea has torn Sicily from Italy, Cyprus from Syria, Eubœa from Bœotia, Atalante and Macris from Eubœa, Besbycus from Bithynia, and Leucosia from the promontory of the Sirens.

CHAP. 91. —ISLANDS WHICH HAVE BEEN UNITED TO THE MAIN LAND.

Again, islands are taken from the sea and added to the main land; Antissa to Lesbos, Zephyrium to Halicarnassus, Æthusa to Myndus, Dromiscus and Perne to Miletus, Narthecusa to the promontory of Parthenium. Hybanda, which was formerly an island of Ionia, is now 200 stadia distant from the sea. Syries is now become a part of Ephesus, and, in the same neighbourhood, Derasidas and Sophonia form part of Magnesia; while Epidaurus and Oricum are no longer islands.

CHAP. 92. —LANDS WHICH HAVE BEEN TOTALLY CHANGED INTO SEAS.

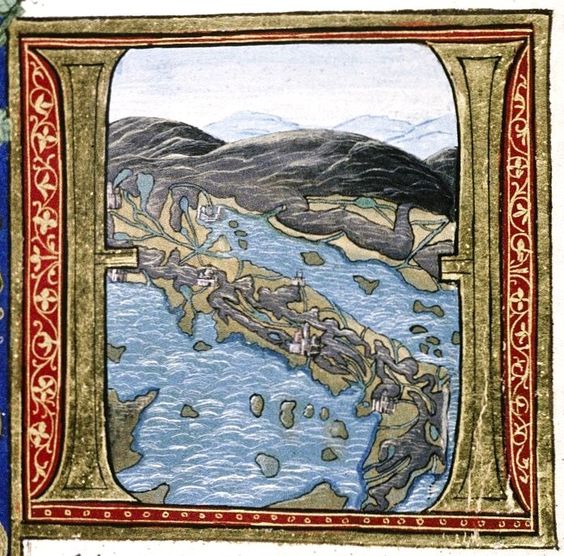

The sea has totally carried off certain lands, and first of all, if we are to believe Plato, for an immense space where the Atlantic ocean is now extended. More lately we see what has been produced by our inland sea; Acarnania has been overwhelmed by the Ambracian gulf, Achaia by the Corinthian, Europe and Asia by the Propontis and Pontus. And besides these, the sea has rent asunder Leucas, Antirrhium, the Hellespont, and the two Bosphori.

CHAP. 93. —LANDS WHICH HAVE BEEN SWALLOWED UP.

And not to speak of bays and gulfs, the earth feeds on itself; it has devoured the very high mountain of Cybotus, with the town of Curites; also Sipylus in Magnesia, and formerly, in the same place, a very celebrated city, which was called Tantalis; also the land belonging to the cities Galanis and Gamales in Phœnicia, together with the cities themselves; also Phegium, the most lofty ridge in Æthiopia. Nor are the shores of the sea more to be depended upon.

CHAP. 94.—CITIES WHICH HAVE BEEN ABSORBED BY THE SEA.

The sea near the Palus Mæotis has carried away Pyrrha and Antissa, also Elice and Bura in the gulf of Corinth, traces of which places are visible in the ocean. From the island Cea it has seized on 30,000 paces, which were suddenly torn off, with many persons on them. In Sicily also the half of the city of Tyndaris, and all the part of Italy which is wanting; in like manner it carried off Eleusina in Bœotia.

CHAP. 95.—OF VENTS IN THE EARTH.

But let us say no more of earthquakes and of whatever may be regarded as the sepulchres of cities; let us rather speak of the wonders of the earth than of the crimes of nature. But, by Hercules! the history of the heavens themselves would not be more difficult to relate:—the abundance of metals, so various, so rich, so prolific, rising up during so many ages; when, throughout all the world, so much is, every day, destroyed by fire, by waste, by shipwreck, by wars, and by frauds; and while so much is consumed by luxury and by such a number of people:—the figures on gems, so multiplied in their forms; the variously-coloured spots on certain stones, and the whiteness of others, excluding everything except light:—the virtues of medicinal springs, and the perpetual fires bursting out in so many places, for so many ages:—the exhalation of deadly vapours, either emitted from caverns, or from certain unhealthy districts; some of them fatal to birds alone, as at Soracte, a district near the city; others to all animals, except to man, while others are so to man also, as in the country of Sinuessa and Puteoli. They are generally called vents, and, by some persons, Charon’s sewers, from their exhaling a deadly vapour. Also at Amsanctum, in the country of the Hirpini, at the temple of Mephitis, there is a place which kills all those who enter it. And the same takes place at Hierapolis in Asia, where no one can enter with safety, except the priest of the great Mother of the Gods. In other places there are prophetic caves, where those who are intoxicated with the vapour which rises from them predict future events, as at the most noble of all oracles, Delphi. In which cases, what mortal is there who can assign any other cause, than the divine power of nature, which is everywhere diffused, and thus bursts forth in various places?

CHAP. 96. —OF CERTAIN LANDS WHICH ARE ALWAYS SHAKING, AND OF FLOATING ISLANDS.

There are certain lands which shake when any one passes over them; as in the territory of the Gabii, not far from the city of Rome, there are about 200 acres which shake when cavalry passes over it: the same thing takes place at Reate.

There are certain islands which are always floating, as in the territory of the Cæcubum, and of the above-mentioned Reate, of Mutina, and of Statonia. In the lake of Vadimonis and the waters of Cutiliæ there is a dark wood, which is never seen in the same place for a day and a night together. In Lydia, the islands named Calaminæ are not only driven about by the wind, but may be even pushed at pleasure from place to place, by poles: many citizens saved themselves by this means in the Mithridatic war. There are some small islands in the Nymphæus, called the Dancers, because, when choruses are sung, they are moved by the motions of those who beat time. In the great Italian lake of Tarquinii, there are two islands with groves on them, which are driven about by the wind, so as at one time to exhibit the figure of a triangle and at another of a circle; but they never form a square.